Understanding Hacktivists: The Overlap of Ideology and Cybercrime

By David Sancho

Hacktivist groups are driven by a political or ideological agenda. In the past, their actions were likened to symbolic, digital graffiti. Nowadays, hacktivist groups resemble urban gangs. Previously composed of low-skilled individuals, these groups have evolved into medium- to high-skill teams, often smaller in size but far more capable. The escalation in skill has directly increased the risks posed to organizations.

Let’s take a closer look at today’s hacktivism landscape — how the groups are motivated and organized, and how they align in geopolitical conflicts such as those in Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas/Palestine.

The sheer number of hacktivist groups complicates a comprehensive analysis. Our research looked to gain insights into their motivations, capabilities, and structures; as well as the overlap between hacktivist and cybercriminal activities. They appear to use the latter as a funding mechanism, suggesting a shift toward financial motivations.

Ideological motivations drive most hacktivist activities

Hacktivist groups are defined by distinct political beliefs reflected in both the nature of their attacks and their targets. Unlike cybercriminals, hacktivists typically do not seek financial gain, though we have observed overlaps with cybercrime. For the most part, these groups focus on advancing their political agendas, which vary in transparency. Broadly, their motivations can be classified into four distinct groups: ideological, political, nationalistic, and opportunistic. While some groups strictly align with one category, others pursue multiple agendas, often with a primary focus supplemented by secondary causes.

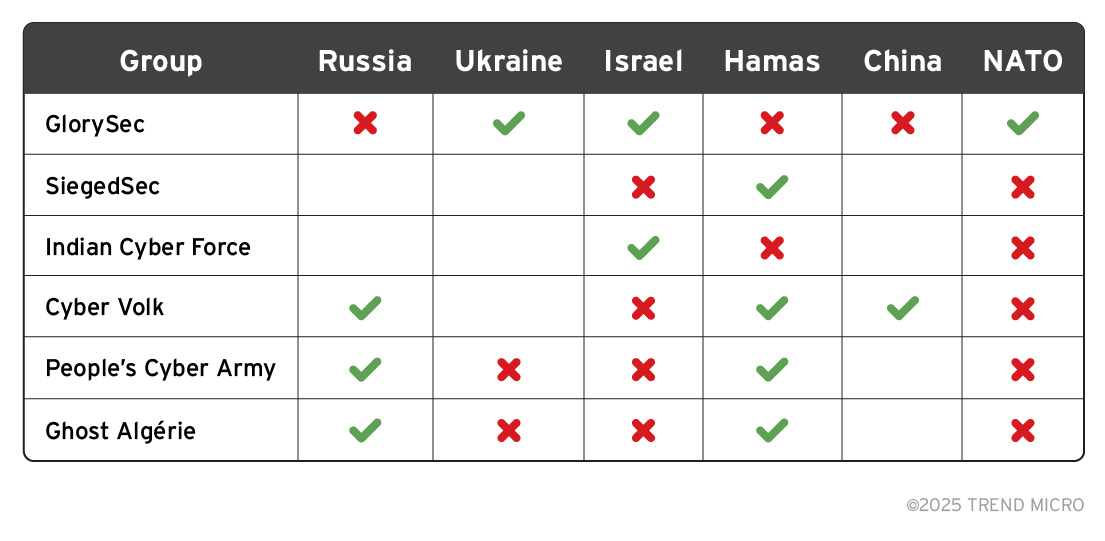

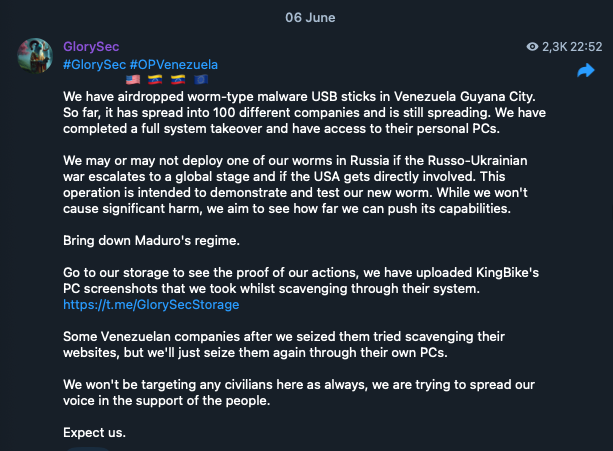

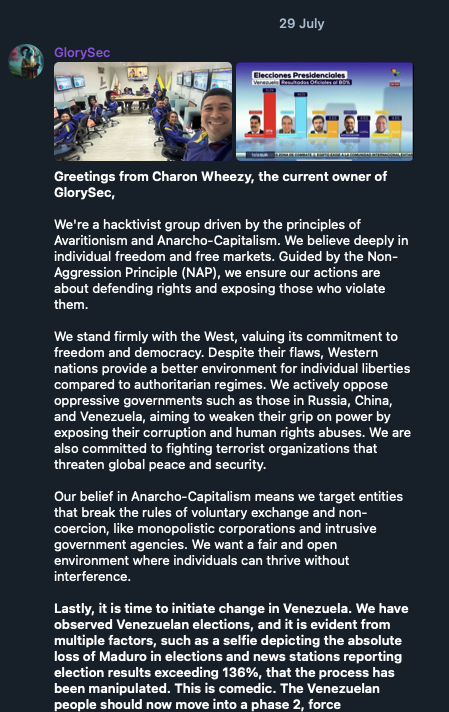

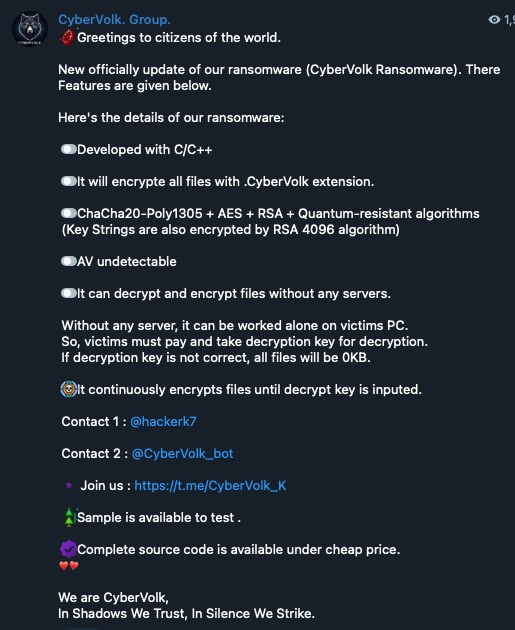

Ideological motivations drive the most hacktivist activity. These groups target entities that challenge their worldviews, often focusing on religious beliefs or geopolitical conflicts. Recent conflicts reveal deep ideological divides. For example, pro-Russian group “NoName057(16)” (tracked by Trend Micro as Wind Hieracosphinx) accuses those who help Ukraine as “supporting Ukrainian nazis”, while Russian critics “GlorySec” (tracked by Trend Micro as Wind Jorogumo) claim to “support Western society in every way” and therefore “oppose the Russian regime”. GlorySec, possibly a Venezuelan group self-described as anarcho-capitalists, “believe in individual freedom and free markets” and therefore oppose countries like Russia and China as well as what they label “their proxy regimes” such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Houthi, Hezbollah, and Hamas.

Figure 1. The GlorySec owner introducing the group’s motivations and stance

Figure 2. The GlorySec group explaining their views and agenda

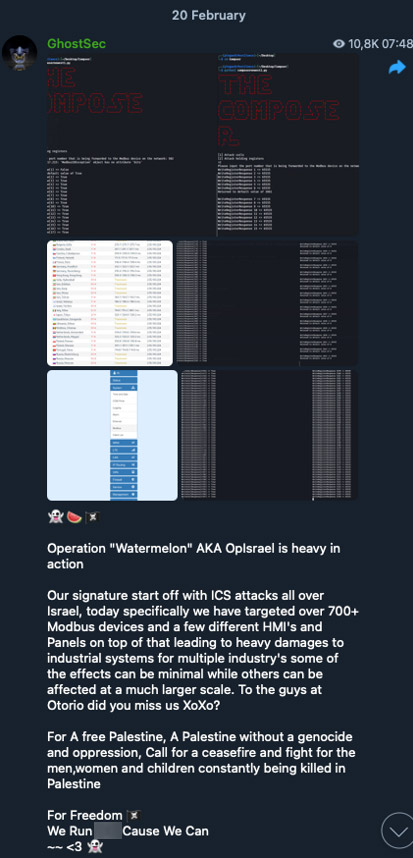

In the Israel-Hamas conflict, some groups explicitly justify their actions. For instance, “GhostSec” describes their mission as: “For a free Palestine. A Palestine without a genocide and oppression. Call for a ceasefire and fight for the men, women and children constantly being killed in Palestine”. Similarly, “CyberVolk” (tracked by Trend Micro as Water Amaroq) frames their attacks as part of a “jihad” “to liberate all of Palestine from the occupying Zionists and their agents in NATO”.

Religiously motivated stance on conflicts mirrors other examples. The “Indian Cyber Force” targets Pakistan, labeling it as a “terrorist country”, claiming that “Malaysia, UAE, Indonesia and Indian Muslims are much better than Pakistani Muslims”. This was their sole justification for defacing a pharmaceutical company in Pakistan.

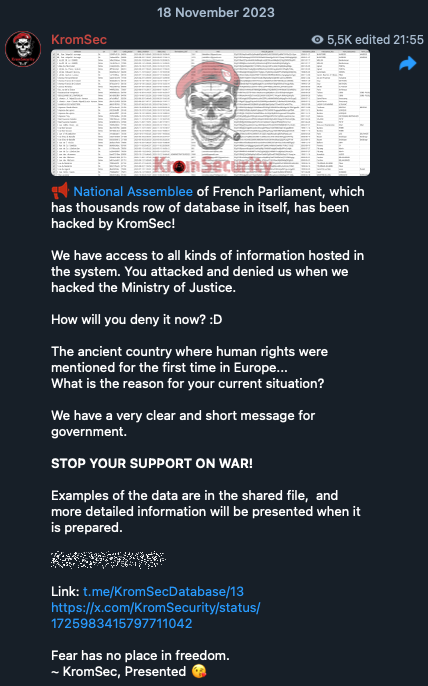

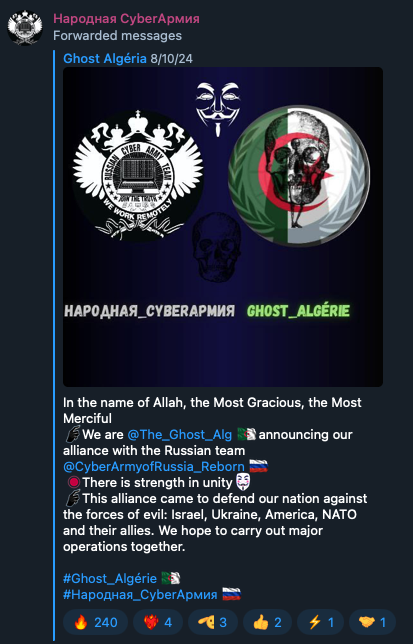

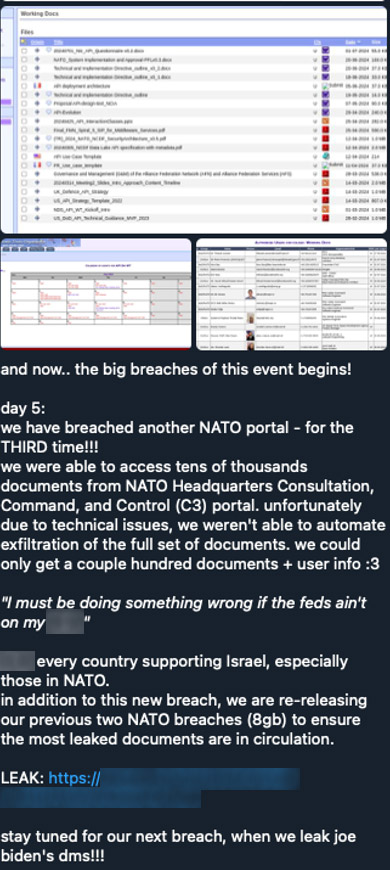

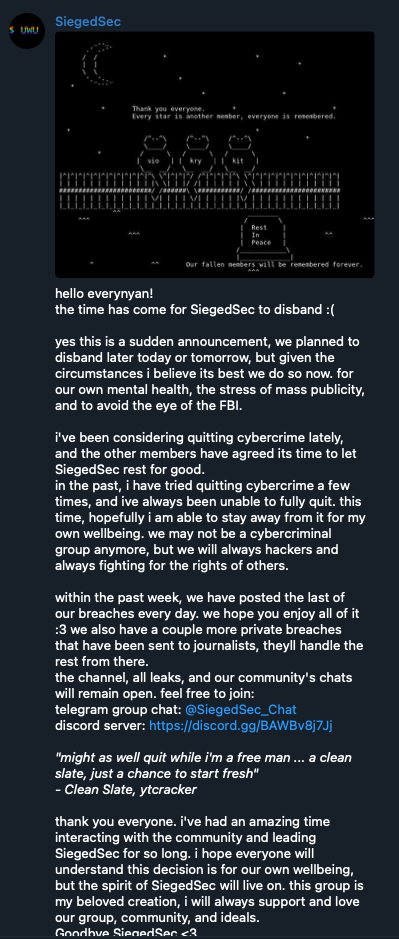

Another group, “SiegedSec”, targeted a NATO web portal and leaked internal data, justifying it with the claim that “NATO supports Israel”. Many groups provide little more than one-liners or vague ideological reasoning for their attacks, such as when the Israeli-aligned group “KromSec” claimed responsibility for an attack against the National Assembly of the French Parliament, stating only that the institution is “supporting war”. Similarly, the Russia-aligned “NoName057(16)” attacked critical infrastructure in Slovenia, justifying it as retaliation for the Slovenian government’s “support of the Ukrainian regime, which we consider criminal, led by Zelensky”. The pro-Russian group “People's CyberArmy ” (tracked by Trend Micro as Wind FengHuang) recently allied with Algeria-based “Ghost_Algérie”, citing shared animosity toward Israel, Ukraine and NATO countries.

Pro-Israel group “We Red Evils” targets infrastructure of their perceived enemies, Lebanon and Bangladesh. While they offer no explicit reason, their tendency to target Muslim-majority countries suggests ideological motivations, though their actions might also be nationalistic by targeting Israel’s declared enemies.

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to first slide

Figure 10. We Red Evils announcing their attack on a telecommunications company in Bangladesh; the Hebrew text reads: “We, Red Evils, are watching you closely and we are deep in your systems.”

Politically motivated hacktivism aims to influence government policies

Some hacktivist groups seek to influence government policies or political outcomes, though such attacks are less common than ideological ones.

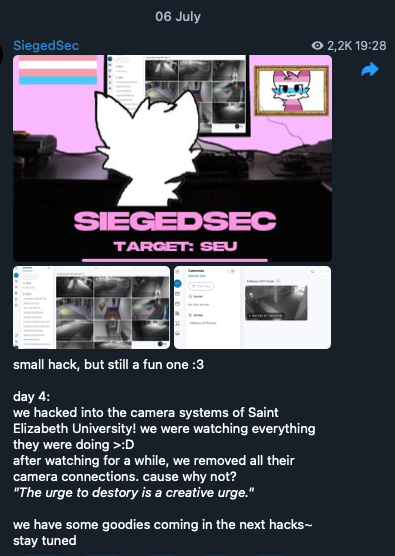

For example, “SiegedSec” targeted Project 2025, an initiative promoting conservative policies. They justified a hack and subsequent leak of a 200GB database by claiming that the project “threatens the right of abortion healthcare and LGBTQ+ communities in particular”. SiegedSec has also been active in #OpTransRights, targeting organizations they perceive as opposing transgender and transsexual rights in the US.

Figure 11. SiegedSec explaining their political motivations

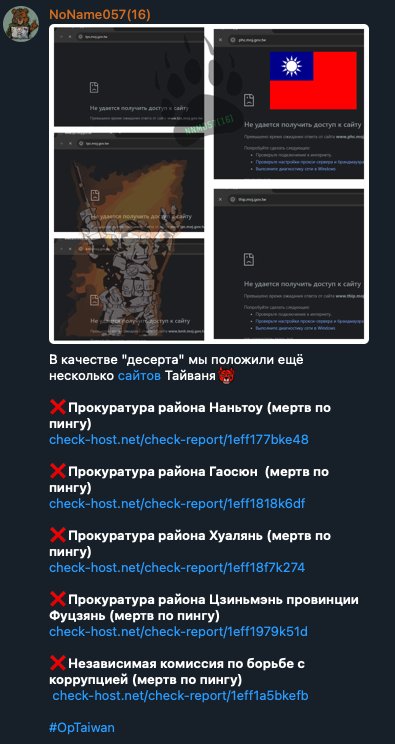

Similarly, “GlorySec” aligned with Taiwan in their efforts to disengage from China, initiating #OpPRC to attack Chinese companies. They stated that “The PRC is a fake country; it should be the ROC”, referring to the self-designations of China (PRC) and Taiwan (ROC). GlorySec is neither Chinese nor Taiwanese. Ironically, Russian hackers have conducted #OpTaiwan for the opposite reason — supporting China.

Figure 12. GlorySec explaining their participation in #OpPRC

Figure 13. NoName057(16) announcing distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks on Taiwanese sites following #OpTaiwan

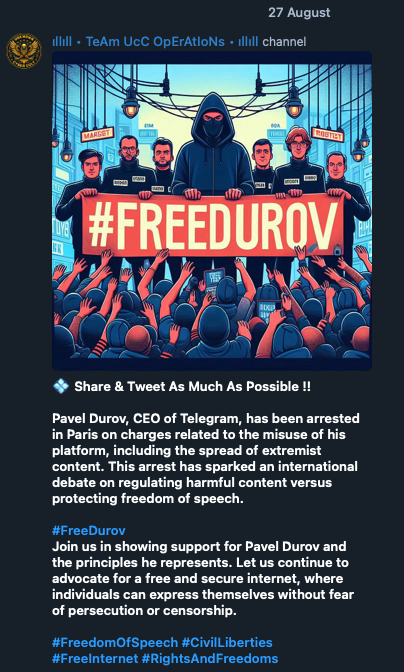

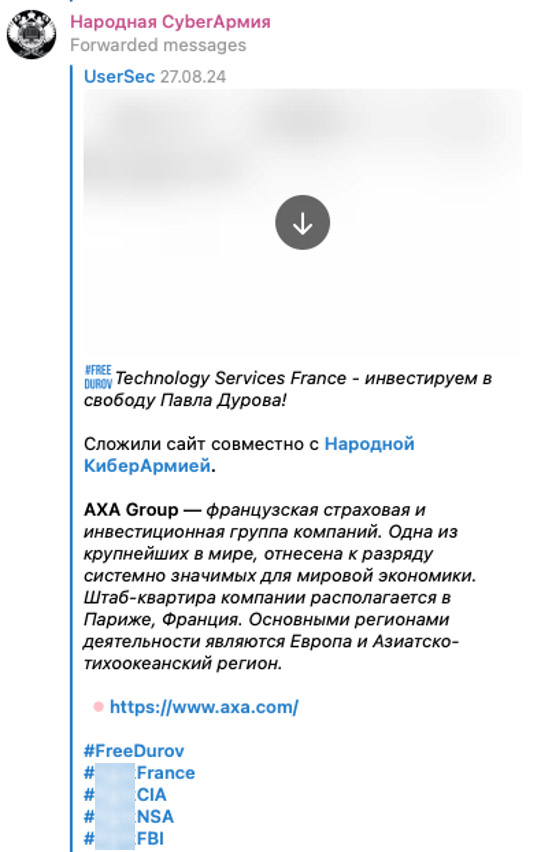

In August 2024, following the arrest of Telegram’s CEO, Pavel Durov, in France, several groups launched a #FreeDurov campaign, citing free speech infringements. As part of this effort, we saw People's CyberArmy initiating attacks against a French company, demanding Durov’s release.

Figure 14. Pro-India group Team UCC announcing their support for Durov

Figure 15. People's CyberArmy claiming responsibility for an attack against a French company as part of the #FreeDurov campaign

Nationalistic hacktivism defends or promotes specific countries’ interests

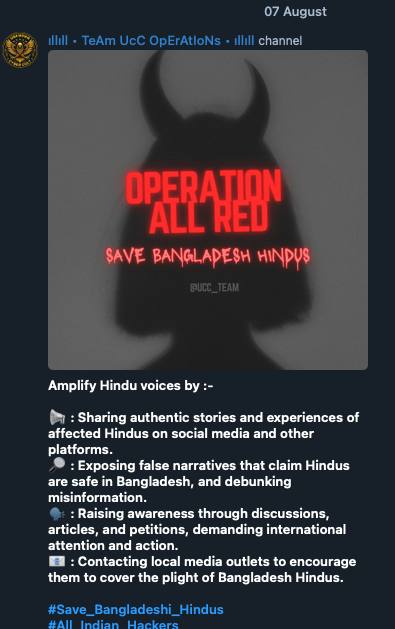

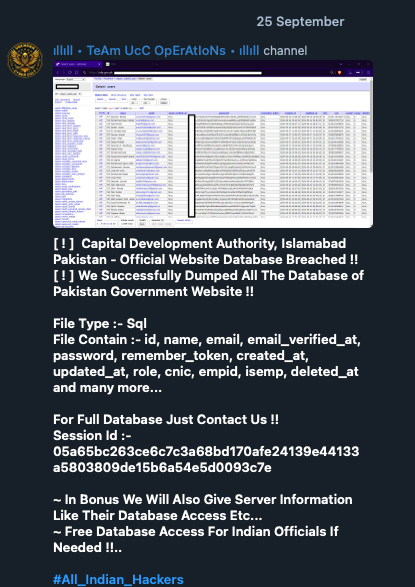

Nationalistic hacktivist attacks are less common and often incorporate cultural symbols and patriotic rhetoric to justify their actions. For instance, the Indian “Team UCC” group claims to “amplify Hindu voices” by “exposing false narratives that claim Hindus are safe in Bangladesh”. They position themselves as defenders of Hindus worldwide, particularly in Bangladesh. They attack Pakistani government websites and organizations as efforts to “defend the Indian cyberspace”.

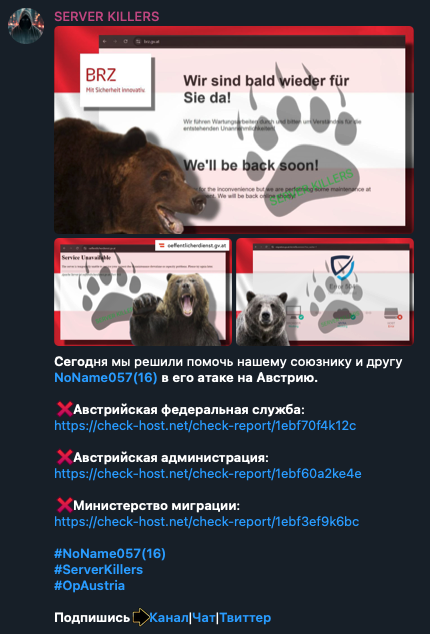

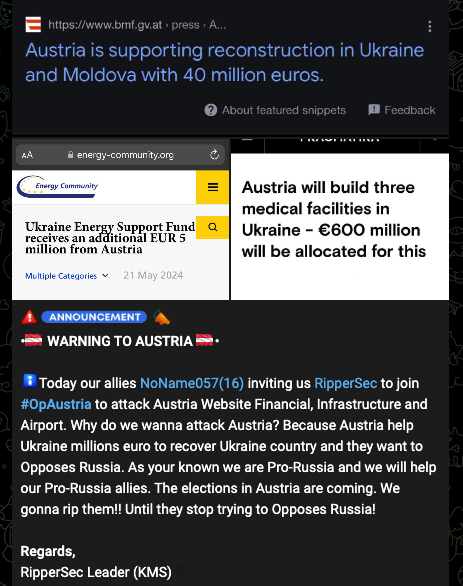

Similarly, many pro-Russia groups exhibit nationalistic motivations. Announcements of their attacks often feature Russian flags, bears as symbols of national pride, and expressions about defending Russia.

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

Figure 19. Pro-Russia group “Server Killers” announcing an attack against Austria by using images of a bear and the bear pawprint

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

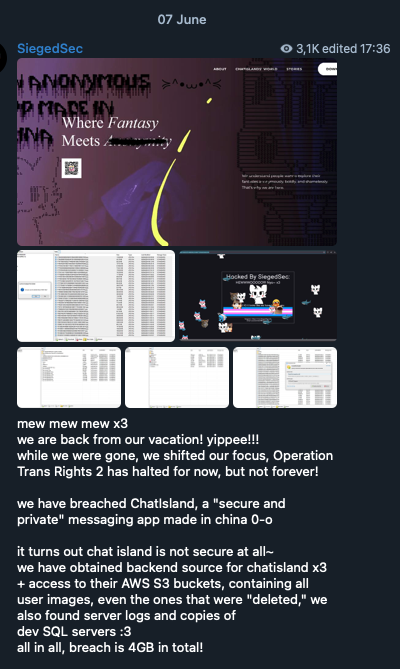

Opportunistic hacktivists exploit easy targets

Some hacktivist groups act purely opportunistically, targeting organizations simply because they are easy to hack. For example, SiegedSec hacked into a messaging application’s website, citing that “it’s not secure at all”. The app being “made in China” might have compounded their motivation, but the group mentioned getting “access to their AWS S3 buckets”, suggesting that the attack required minimal effort rather than a justification. These groups often appear to consist of younger people driven by righteous anger, which manifests as entitlement and a belief that any hack is fair game.

Figure 21. SiegedSec describing their attack on a messaging app’s website

Hacktivist motivations also overlap and cross over

Hacktivist groups generally stem from a single ideology or a specific cause. To illustrate, People's CyberArmy backs Russia in the Ukraine conflict, Indian Cyber Force advances Indian interests, and “Cyb3r Drag0nz” is pro-Hamas and anti-Israel. However, some align with causes outside their main focus. For instance, the Russia-Ukraine divide is largely regional: Pro-Russia groups are mostly from Russia, while global hacktivists tend to be pro-Ukraine. In contrast, the Israel-Hamas conflict polarizes groups along religious lines. Muslim-aligned groups like “AnonGhost Indonesia” side with Hamas/Palestine, while others, like Team UCC, back Israel while opposing Pakistani Muslim causes.

These crossovers also show alliances shifting along political and ideological axes. Pro-Russia groups often side with China against Taiwan and oppose Israel, aligning with Russia’s broader adversarial stance without explicitly stating reasons. For example, “Russian Cyber Army” allies with many anti-Israel, pro-Arab regional groups; and SiegedSec, despite advocating LGBTQ+ rights, express anti-Israel sentiments even though they don’t seem to be from the Middle East. GlorySec, a seemingly Venezuelan group opposing its local left-wing government, aligns with Ukraine, NATO, and Israel, reflecting its economic liberalist stance while seeming to be unsupportive of the “trans” agenda.

Motivations often cascade — first with regional causes, then religious beliefs, followed by political ideologies. This interplay blurs lines between hacktivism and state influence. Some experts suggest that nation-states might be funding these groups, using them as civil militias to further nationalistic goals. If true, these hacktivists might unknowingly serve as pawns in a larger geopolitical landscape.

To summarize these dynamics, we compiled a table showing groups spanning multiple conflicts:

Table 1. Hacktivist groups with overlapping motivations

Note: [checks] mean “for,” [x] means “against,” and an empty field means unknown

How hacktivists execute their objectives: Tools, capabilities, strategies

DDoS

Hacktivist groups typically rely on DDoS and web defacement attacks, which are orchestrated by the group and executed by volunteers using HTTP stress tools. Originally designed for web administrators to test server capacity, these tools are abused to flood servers with malicious traffic, causing disruptions.

Taking down a target web site is a favored tactic due to its simplicity, though its impact is often limited. DDoS attacks are time-bound, and their effects on organizational websites are usually short-lived. While sustained attacks on revenue-generating sites (e.g., online shops, casinos), during peak times can cause significant harm, most targets are government or corporate websites, resulting in minimal reputational damage.

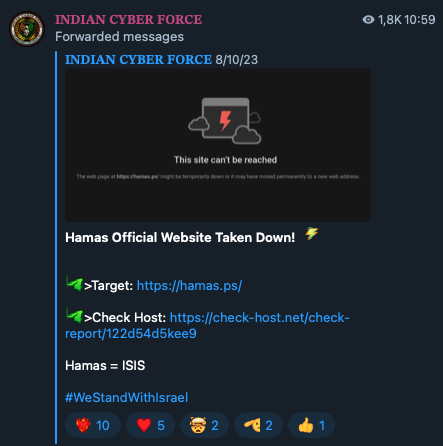

Figure 22. Indian Cyber Forces targeting a Hamas site with DDoS

Web defacement

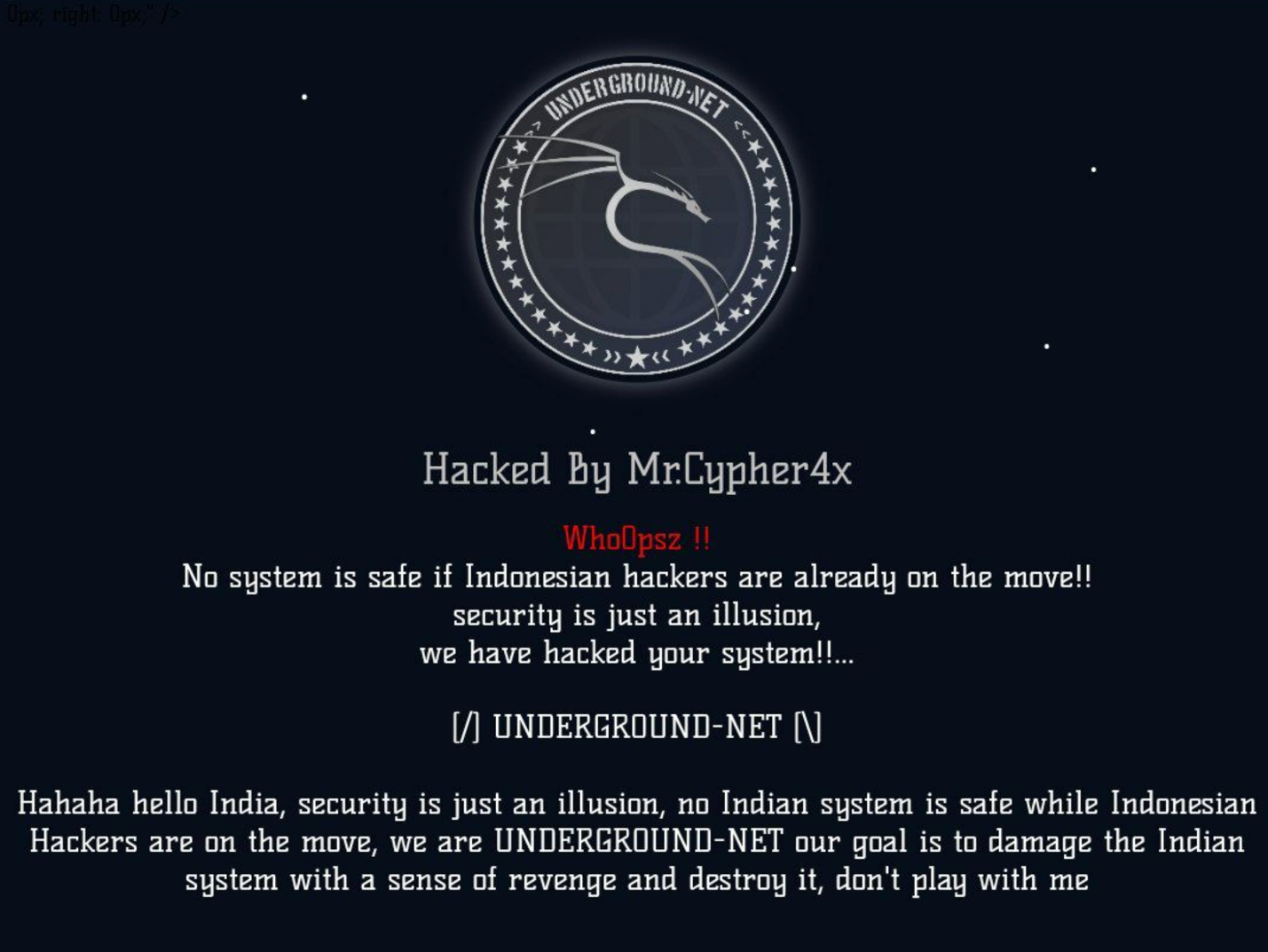

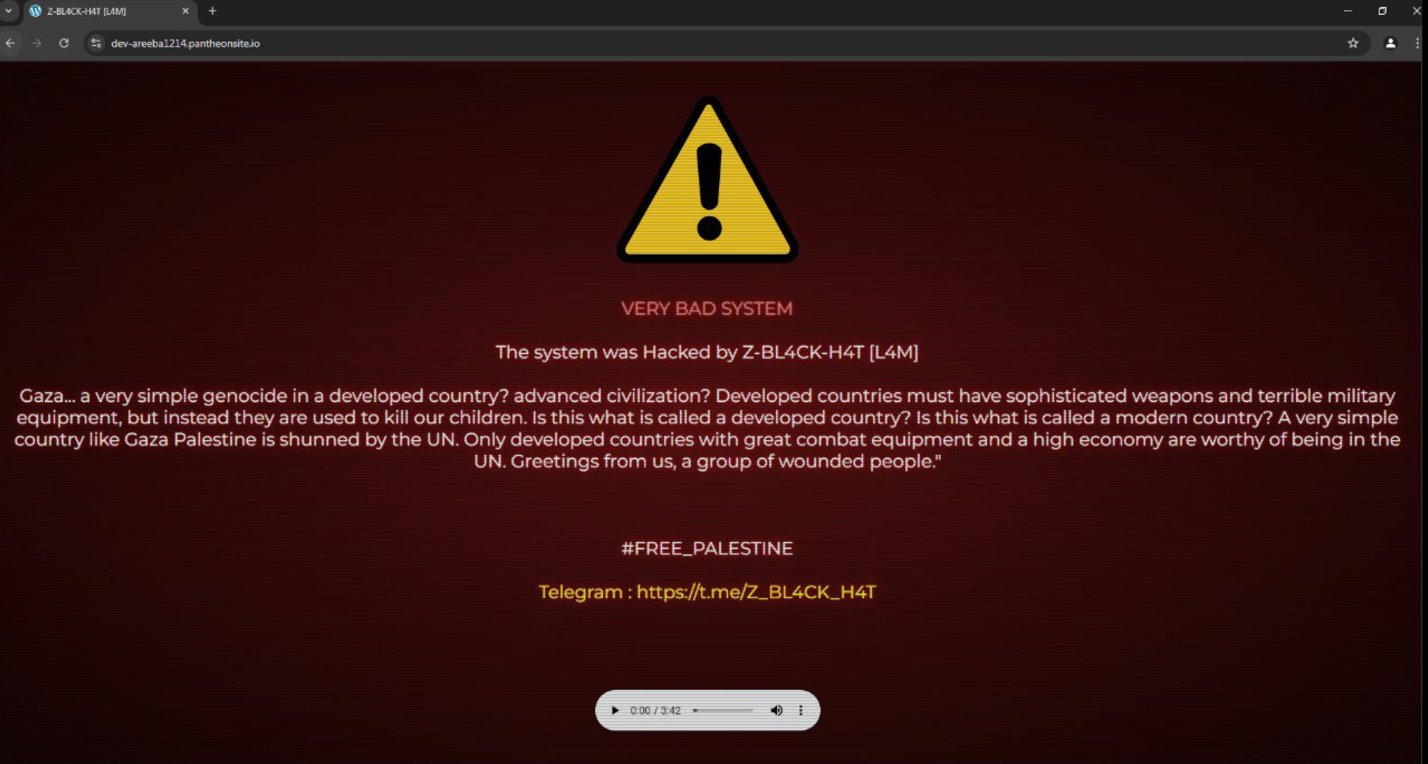

Hacktivist groups have used web defacement for a very long time. In these attacks, the target website’s front page is replaced with content such as hack announcements, authorship claims (i.e., “hacked by”), or explanations of the attack’s motive. Web defacements are usually short-lived with limited impact, primarily affecting the reputation of the organization behind the targeted site.

Figure 23. “underground-net”, an Indonesian group, defacing an Indian site

Figure 24. “Z-BlackHat” defacing an Israel site, citing a pro-Palestinian motive

Hack and leak

Today’s hacktivist groups increasingly engage in “hack-and-leak” attacks, which are more sophisticated than DDoS, and web defacements. They hack networks and servers to exfiltrate data, which is then shared publicly via file-sharing platforms. These attacks are frequently promoted on the group’s Telegram channel. The advanced nature of these operations suggests a more complex recruitment process, prioritizing members with more offensive hacking skills.

Infrastructure hacking

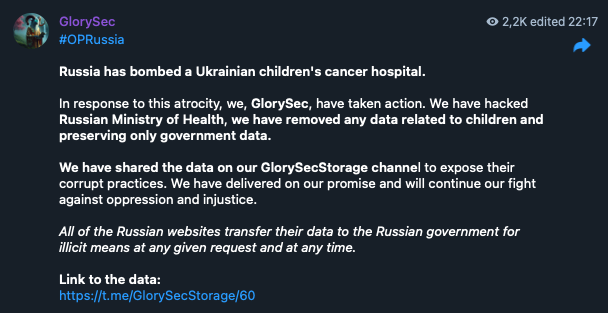

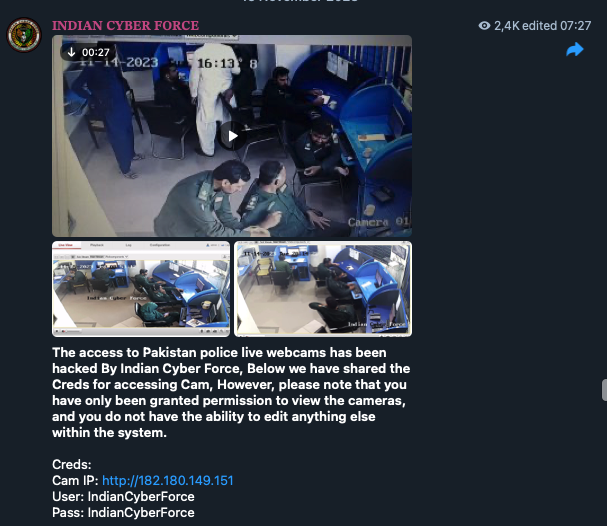

Hacktivist groups also target physical infrastructure to demonstrate their offensive capabilities and undermine the victim’s defenses. For example, Indian Cyber Force claimed to have hacked into Pakistan’s police camera system. Similarly, “Cyber Av3ngers” leaked an internal network map of a critical infrastructure site they compromised. This group was notorious for their December 2023 attack on an Irish water treatment facility that left residents without drinking water for two days. Ireland was not their real target, but a company using Israeli-made equipment. In another case, a pro-Ukrainian group reportedly attacked Belarusian railway infrastructure in 2022 news to disrupt Russian troop movements, though we could not confirm this attack with any real announcement from the group.

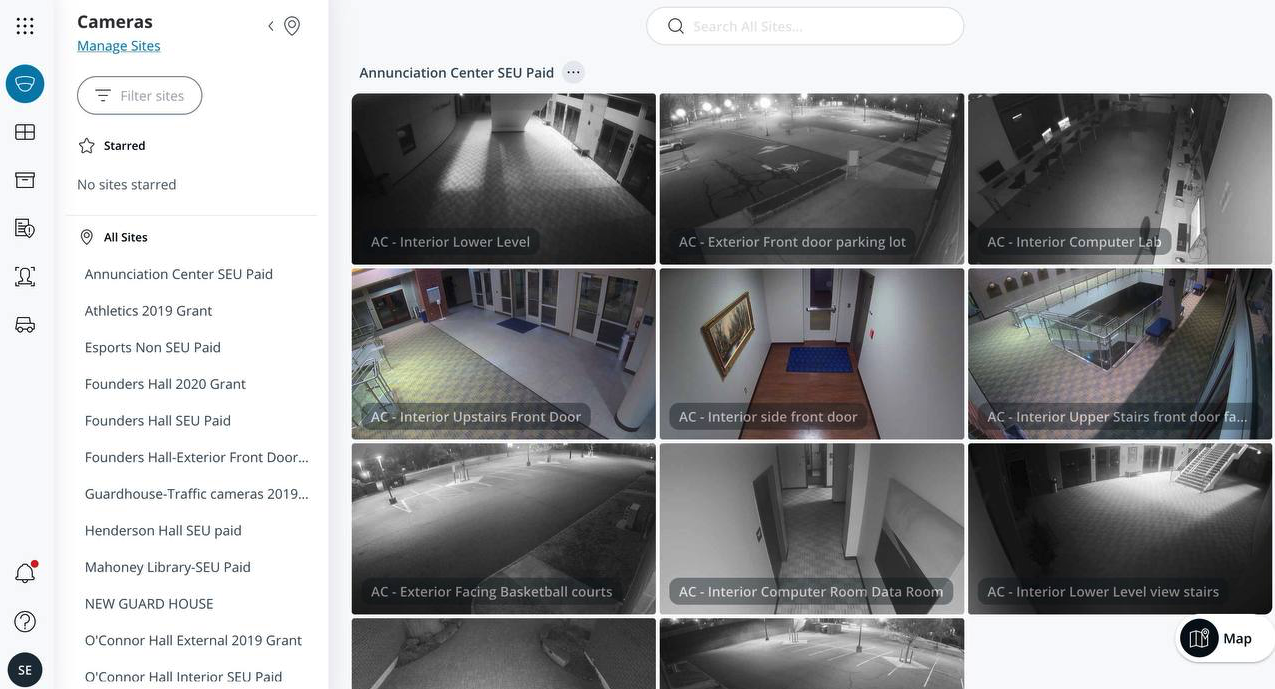

Opportunistic attacks are also common. For instance, SiegedSec hacked into a university’s camera system, displaying altered locations tagged “HACKED BY SIEGEDSEC” in screenshots. The lack of a clear motive suggests this was a demonstration of capability rather than a targeted operation.

Figure 29. Indian Cyber Force showing footage of hacked web cameras

Go to last slide Go to next slide- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

- Go to previous slide Go to next slide

Malware

Malware attacks are rare among hacktivist groups, likely because creating and deploying malware is more complex than quick, reputation-focused attacks. Still, some groups develop ransomware to fund their activities.

An example is the pro-Ukraine “Twelve” reportedly operating like a ransomware group. Unlike cybercriminals asking for ransom, the malware they use encrypts, deletes and exfiltrates data, with the stolen information shared on a Telegram channel. However, we have not found this channel or verified the group’s deeper motivations.

In another case, GlorySec placed malware on USB sticks in a Venezuelan city and allegedly gained access to systems in “100 different companies”.

Figure 34. GlorySec explaining their malware attack

Inside hacktivist groups: Organizational structure, leadership, recruitment

Modern hacktivist groups are typically led by a small core of trusted individuals, often online friends or acquaintances who share technical capabilities and a common political or religious ideology that defines the group’s alignment.

For instance, GlorySec’s supposed owner, using the alias “Charon Wheezy,” describes the group’s principles in a post that includes a selfie with others in a computer-filled room. SiegedSec’s founder, known as “Vio,” describes the group as “gay furry hackers” and identifies as “a former member of GhostSec and Anonymous Sudan”. These introductions are a common starting point for recruiting other hackers who share the same ideology and inclinations.

Figure 35. GlorySec’s owner explaining the group’s organizational structure

Figure 36. Personal profile of SiegedSec’s founder

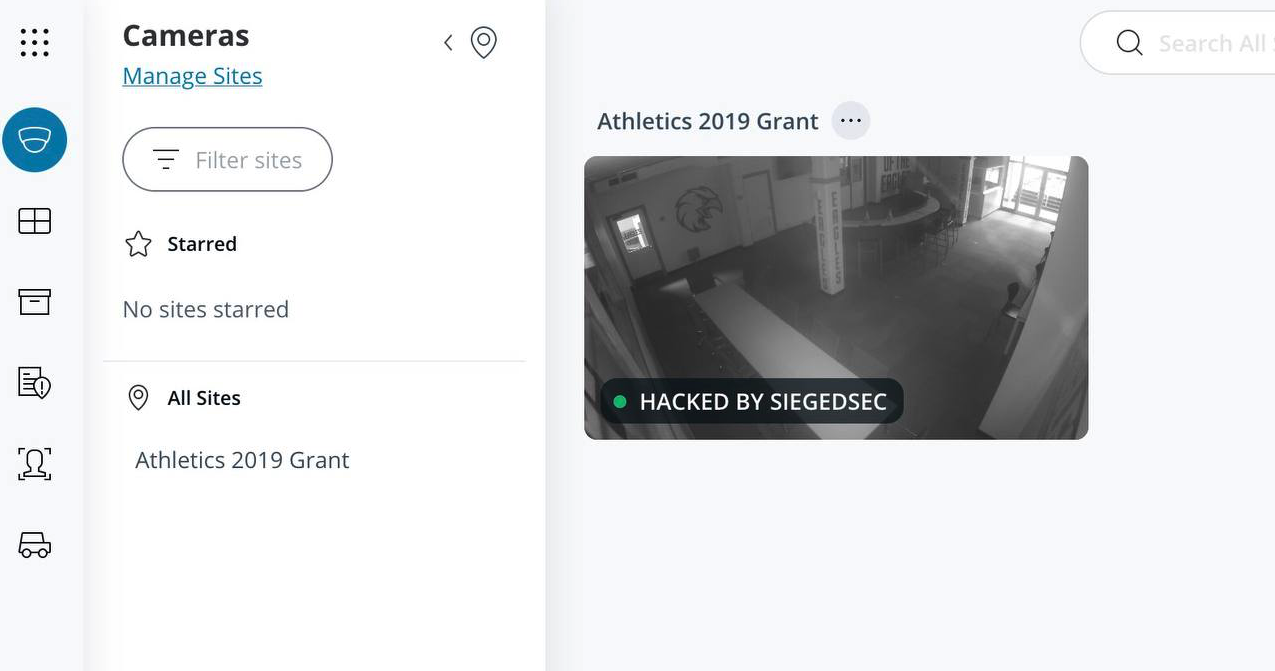

Recruitment strategies vary. Some groups such as CyberVolk openly advertise for members, partnerships, and paid promotions. Others, like GlorySec, seek insiders (“moles”) from rival nations such as China, Venezuela, or Russia, to access “government or company management systems”. They mention that they have US$200,000 to pay for this, also offering that the mole “can be reallocated” (we understand this to mean relocated) “if any problems arise”.

The groups’ leaders, which appear to be very few, vet members personally and recruit directly via announcement channels. They perceive their actions as defending ideals rather than committing crimes. However, fear of legal repercussions is common. Groups often disband, rebrand, or take evasive actions when under scrutiny, particularly if they are based in the US or Europe. SiegedSec, for instance, disbanded in July 2024, acknowledging their actions as cybercriminal and citing fear of “the eye of the FBI”.

When hacktivism and cybercrime overlap

The most apparent link we have seen between hacktivism and cybercrime is ransomware. Some groups, like “Ikaruz Red Team” and their affiliates, use leaked versions of major ransomware programs, such as LockBit, to target organizations. While their motives are unclear, they don’t appear to be financial.

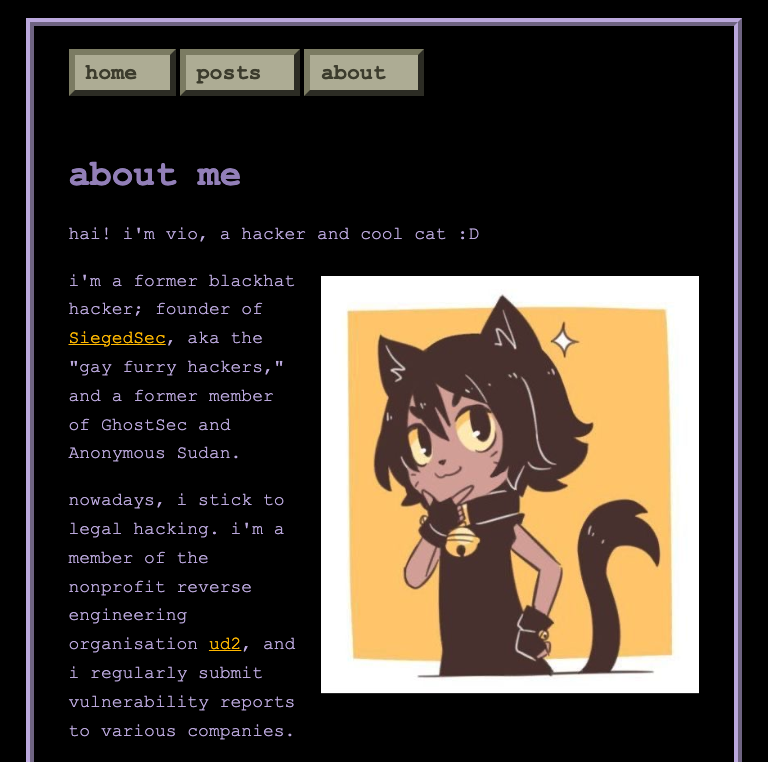

Certain groups have also launched ransomware affiliate programs to fund their operations, though these efforts remain niche and lack strong connections to top-tier cybercrime operations. For example, CyberVolk promoted its “CyberVolk Ransomware”, claiming that it was “AV undetectable” and even selling its source code for a “cheap price”.

Figure 40. CyberVolk providing details of its ransomware program

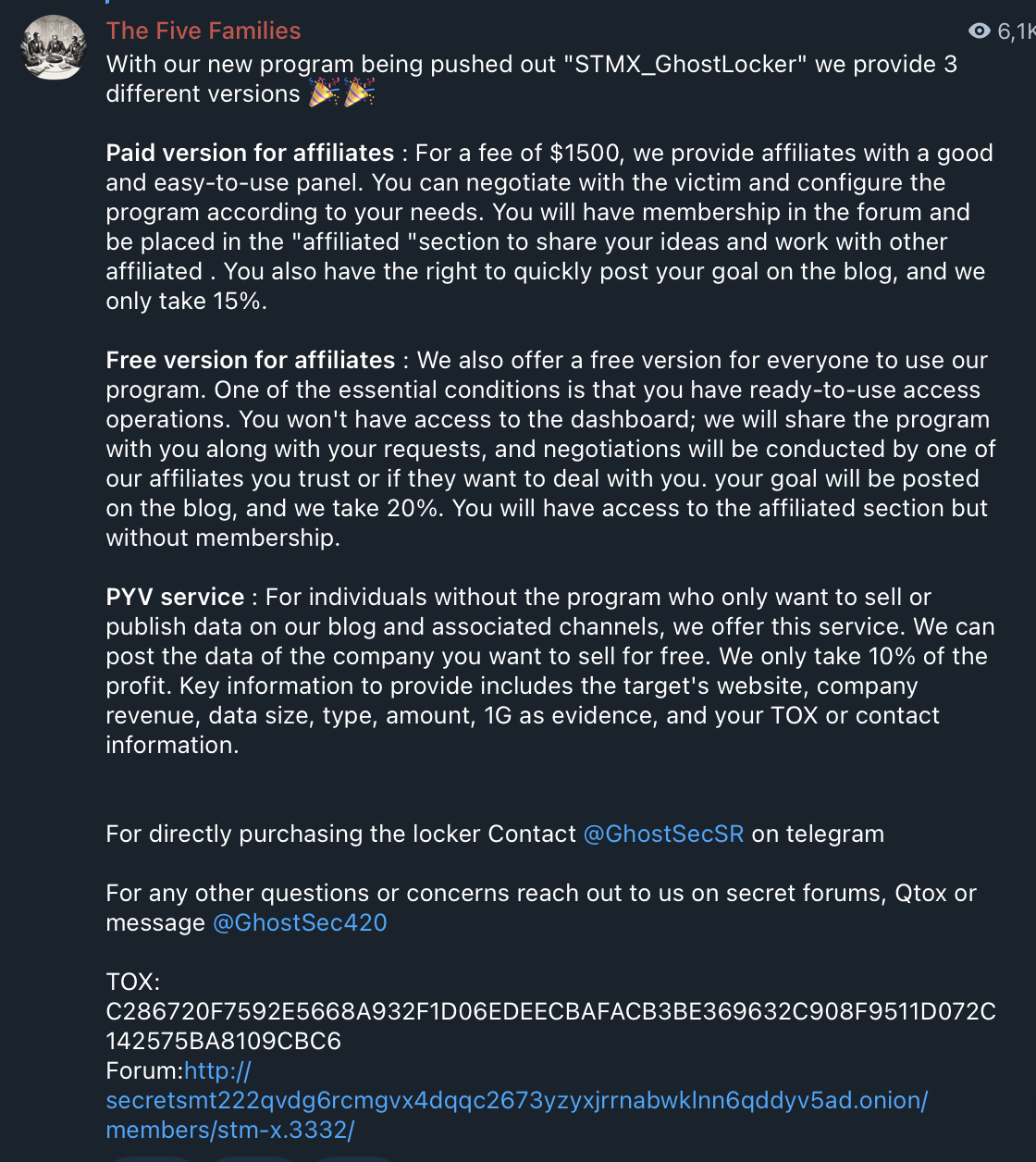

Similarly, a meta-group “The Five Families” — comprising “ThreatSec”, GhostSec, “Stormous”(tracked by Trend Micro as Water Garuda), “Blackforums” and SiegedSec — offered a ransomware named “SMTX_GhostLocker”, which seems to be developed by GhostSec. Another now-defunct group, “1915 Team”, previously promoted a “Zagros Ransomware” affiliate program before disbanding and shutting down their Telegram channel.

Figure 41. The Five Families explaining their ransomware program

Conclusion

Modern hacktivist groups are small, skilled cells united by shared ideologies — regional, religious, or political — that dictate their targets. DDoS and web defacements are still a staple in their arsenal, though hack-and-leak attacks are now increasingly prominent.

Targets are chosen based on belief systems, and often include government organizations, companies in territories they perceive as enemies, and even those using equipment made by their adversaries. Their attacks aim to tarnish the enemy’s brand. This aligns closely with some of the nation-states’ political agendas, which raises questions about whether certain groups are influenced or funded by governments.

For businesses and enterprises, the threat is unpredictable. Hacktivists might attack for political reasons — or none at all. They can target organizations regardless of their political stance. As volatile players in the cyber arena, they add layers of uncertainties and risks to today’s security challenges.

Even organizations with no obvious reason to fear politically motivated attacks are not immune to hacktivist threats. To minimize exposure, companies should take proactive steps, including:

- Investing in DDoS protection. If uptime is crucial to operations, consider this as an insurance policy to maintain continuity.

- Securing web-facing assets. Document and fully patch external systems to reduce the risk of defacements and other attacks.

- Implementing attack surface risk management (ASRM). Deploy tools to monitor entry points, which helps minimize hacking attempts.

- Draw from industry expertise. Enhance preparedness against hacktivism and similar threats through resources that provide guidance for organizations during times of conflict.

Trend Vision One™ Threat Intelligence

To stay ahead of evolving threats, Trend Vision One™ customers can access a range of Intelligence Reports and Threat Insights within Vision One. Threat Insights helps customers stay ahead of cyber threats before they happen and allows them to prepare for emerging threats by offering comprehensive information on threat actors, their malicious activities, and their techniques. By leveraging this intelligence, customers can take proactive steps to protect their environments, mitigate risks, and effectively respond to threats.

Trend Vision One Intelligence Reports App [IOC Sweeping]

CyberVolk | A Deep Dive into the Hacktivists, Tools and Ransomware Fueling Pro-Russian Cyber Attacks

CyberVolk Ransomware: Understanding the Threat from Pro-Russian Hacker Groups

CyberVolk Ransomware

DDOSIA - NONAME057(16); JAN 2024 PROTOCOL UPDATE

DDoSia - NoName057(16); Dec 2023 protocol update

NoName057(16) targets Italian Organisations with DDOSIA

GhostSec’s joint ransomware operation and evolution of their arsenal

Trend Vision One Threat Insights App

Threat Actors:

Emerging Threats:

- CyberVolk Ransomware: Understanding the Threat from Pro-Russian Hacker Groups.

- CyberVolk | A Deep Dive into the Hacktivists, Tools and Ransomware Fueling Pro-Russian Cyber Attacks

Hunting Queries

Trend Vision One Search App

Trend Vision Once Customers can use the Search App to match or hunt the malicious indicators mentioned in this article with data in their environment.

CyberVolk Ransomware Detection Query

*CYBERVOLK* AND eventName:MALWARE_DETECTION AND LogType: detection

Stormous Ransomware Detection Query

*STORMCRY* AND eventName:MALWARE_DETECTION AND LogType: detection

More hunting queries are available for Vision One customers with Threat Insights Entitlement enabled

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

HttpContext.GetGlobalResourceObject("ES","RelatedPosts")%>

HttpContext.GetGlobalResourceObject("ES","RecentPosts")%>

- Estimating Future Risk Outbreaks at Scale in Real-World Deployments

- The Next Phase of Cybercrime: Agentic AI and the Shift to Autonomous Criminal Operations

- Reimagining Fraud Operations: The Rise of AI-Powered Scam Assembly Lines

- The Devil Reviews Xanthorox: A Criminal-Focused Analysis of the Latest Malicious LLM Offering

- AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce

Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One

Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One