Ransomware: 10 Years of Bullying, Fear-mongering and Extortion

It's been around a decade since we've been introduced to ransomware, the malicious piece of software that takes its victim's most important files and keeps it hostage in exchange for a ransom (hence its name). To mark this milestone for one of the most bullish, money-hungry malware types ever, let's take a stroll down memory lane to see how it has evolved through some of the notable cases we've tackled through the years.

It's been around a decade since we've been introduced to ransomware, the malicious piece of software that takes its victim's most important files and keeps it hostage in exchange for a ransom (hence its name). To mark this milestone for one of the most bullish, money-hungry malware types ever, let's take a stroll down memory lane to see how it has evolved through some of the notable cases we've tackled through the years.

2006: The Beginning

While cases of ransomware attacks have been reported by the media as far back as mid-2005, more sophisticated versions that featured some form of encryption started to emerge a year later, in 2006. One of these early variants, which we reported and detected as TROJ_CRYPZIP.A, searched through its victim's hard drive for files with certain file extensions. It then zips them into password-protected archives before deleting the original. Without backups stored somewhere else, this only left the user with no other extant copy of their files except for the ones in the aforementioned archives. TROJ_CRYPZIP.A also created a notepad file that served as the ransom note, informing users that they can get the password to the archives for US$300.

Of course, seeing as this was one of ransomware’s first attempts at bilking unsuspecting users for money, the scam itself wasn’t all that thought out very well. The password that was being held for ransom could actually be found inside one of the malware’s component files, specifically its .DLL file, in plain view and unencrypted.

2011: The Experimental Years

Fast forward five years later, and we see how ransomware—or at least its payment methods—have evolved to include mobile payment systems. In 2011, TROJ_RANSOM.QOWA was spotted victimizing users in Russia. Instead of taking certain files ransom, this ransomware variant prevented users from accessing their desktops by displaying a homepage that demanded a 360-RUR (around US$12 at the time) ransom. Victims would have to dial a premium number and accept the charges before they would be able to access their systems again.

While this isn’t quite yet the monstrous, file-encrypting beast that ransomware would soon become or one that asked for an exorbitant ransom, it was certainly effective. Despite the US$12 fee, this particular operation was known to collect at least US$30,000 from an estimated 2,500 victims in a span of five weeks. The malware was found to have been downloaded from a pornographic website over 137,000 times only a month earlier, mostly by Russian users.

The low price and easy payment method may have helped make this scheme more palatable to its victims. Would you pay $12 to gain back control of your computer? For roughly the price of three Venti Lattes today—a fraction of the amounts that other ransomware variants have been known to demand—that would have been an easy choice.

These numbers demonstrate ransomware's money-making potential. A cybercriminal scheme that involves tricking people into downloading malware that prevents them from accessing their own files and computers unless they pay up is, evidently, very effective. It also speaks about the value of having an effective distribution method. To put it bluntly, this case showed how pornography managed to hook a lot of Russians into downloading malware.

2012: Puberty and Scare Tactics

2012 would be the year where ransomware blossomed not only in terms of its maliciousness, routines, and general effectiveness, but also in its geographical scope. During this year, ransomware changed the way it took files and computers hostage, and how it demanded payment. It also began hitting targets outside of Russia. It was also this year that ransomware started to use scare tactics in cases that involved Police Ransomware, a.k.a. REVETON, a strain of ransomware that struck victims across Europe and the US.

2012 would be the year where ransomware blossomed not only in terms of its maliciousness, routines, and general effectiveness, but also in its geographical scope. During this year, ransomware changed the way it took files and computers hostage, and how it demanded payment. It also began hitting targets outside of Russia. It was also this year that ransomware started to use scare tactics in cases that involved Police Ransomware, a.k.a. REVETON, a strain of ransomware that struck victims across Europe and the US.

REVETON made users fork over their money by convincing them that they did something illegal (like install pirated software), and as such, they needed to pay a stiff fine or risk being arrested and put into jail. It did this by tracking the geographical location of the victim’s system, which it used to send an appropriate ‘ransom note’ that was written in the victim’s language. The ransom messages also had logos of the victim’s local law enforcement organization (like an FBI message in the US or one from the Gendarme Nationale for users in France) to scare its victims into paying.

Should a victim be skeptical enough to try and ignore this notification, they would still be forced to pay the fine—a hefty US$200 to be sent through wire transfer platforms such as Ukash—since REVETON also locks the entire system down to prevent access to any of its content or applications.

Besides this, REVETON strains spread through compromised websites, which was also new for ransomware.

2013: Full Encrypting Maturity

2013 would then herald what is currently known as ransomware’s most dangerous form: Cryptolocker. Besides locking down the entire system and rendering it useless, this variant also encrypts the files in such a way that it’s impossible to restore them to a usable form without paying the ransom.

2013 would then herald what is currently known as ransomware’s most dangerous form: Cryptolocker. Besides locking down the entire system and rendering it useless, this variant also encrypts the files in such a way that it’s impossible to restore them to a usable form without paying the ransom.

The method involves the use of two encryption methods applied at the same time. The first method used AES (the Advanced Encryption Standard uses one key to encrypt and decrypt data) to encrypt the files in the affected system. Now, if this was all that Cryptolocker used, it would be easy to undo since the user would only need to find that one key, and that key itself is written in the encrypted files. It may take some time and effort, but the encryption can be reversed without needing to pay.

Cryptolocker doesn't stop there, though. It also uses another encryption method, RSA, to encrypt the AES key. RSA is an encryption method that uses two separate keys for encryption and decryption, and in this case, the decryption key stays with the cybercriminal to make it impossible to figure out or guess. Basically, Cryptolocker forces its victims to consider either paying up or losing everything. Unfortunately, this isn't an annoyance that you can fix by paying the $12 ransom. The ransom for this scheme reaches a whopping US$300. With literally no way to skirt the encryption, it can be pretty painful.

[Visualized: See how ransomware infects systems and encrypts data]

2013 also saw ransomware finding new ways to spread itself. Spam campaigns were seen spreading Cryptolocker, using UPATRE and ZBOT strains to infiltrate victims’ systems. We would later discover a variant that was being spread via removable drives, a propagation routine not dissimilar to that used by a Worm malware type (hence its detection name, WORM_CRILOCK.A).

[More: How modern ransomware variants work]

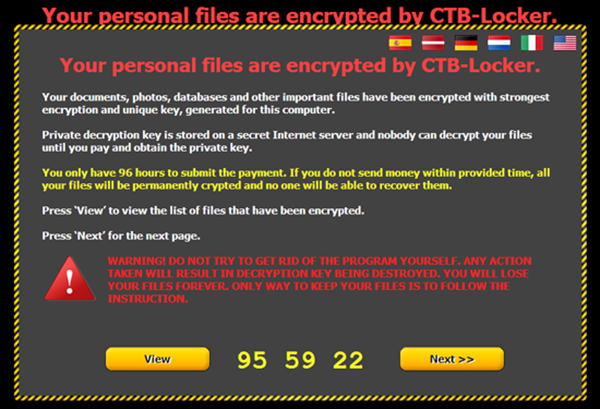

2014-2015: Crypto-ransomware and Cryptocurrency

From here, ransomware’s evolution slowly stagnated after seemingly finding its ‘perfect form’ and keeping to it, but it did add a few tweaks along the way. The start of 2014 saw TROJ_CRYPTRBIT.H, a variant that functioned like Cryptolocker, but with a new twist: victims would now have to pay with Bitcoins rather than through usual money transfer methods. From there, more "improvements" would come up, such as one that came with malware that also stole from the victim’s Bitcoin wallet (CRIBIT), or those that used darknet browsers to cover their tracks (CTBLocker). One of the latest strains, TorrentLocker, would use CAPTCHA code and redirections to phishing websites as an infection method.

From here, ransomware’s evolution slowly stagnated after seemingly finding its ‘perfect form’ and keeping to it, but it did add a few tweaks along the way. The start of 2014 saw TROJ_CRYPTRBIT.H, a variant that functioned like Cryptolocker, but with a new twist: victims would now have to pay with Bitcoins rather than through usual money transfer methods. From there, more "improvements" would come up, such as one that came with malware that also stole from the victim’s Bitcoin wallet (CRIBIT), or those that used darknet browsers to cover their tracks (CTBLocker). One of the latest strains, TorrentLocker, would use CAPTCHA code and redirections to phishing websites as an infection method.

The period between 2014 and 2015 also showed how crypto-ransomware evolved to pounce on enterprise targets, with variants such as CryptoFortress that could encrypt files in shared network resources, and Ransomweb that encrypts websites and web servers. They still work the same way, but the implications are magnified. Having ransomware lock up a family's home computer would be bad enough, with the way it can keep one user from accessing carefully curated music, precious family photos, and maybe a gamer's long-term saved game files. But malware that could stop a company's operation because no one could access their machines? Disastrous.

[More: Crypto-ransomware spreads into new territories]

2015-Present: The Case for a Ransomware-free Future

As a malware type, ransomware is a beast. Being infected with its contemporary strains such as Torrentlocker and CTBLocker would not only be a nightmare for someone invested in their data but also for those without the money to pay the ransom (and we do recommend that you don’t, as it would just be giving these cybercriminals more reason to continue). And at the moment, there is still no one-size-fits-all cure for a ransomware infection. However, you can make sure that you’re protected.

Ransomware Cure and Prevention

Users infected by ransomware should do the following:

- Disable System Restore.

- Run your anti-malware to scan and remove ransomware-related files.

- The Trend Micro AntiRansomware Tool 3.0 works on infected computers, and can be run from a USB drive.

Note that some ransomware variants require extra removal steps such as deleting files in the Windows Recovery Console. Be sure to follow all required steps to completely remove the specific ransomware files your computer has.

To prevent ransomware infections, keep these things in mind:

- Back up your files regularly.

- Apply software patches as soon as they become available. Some ransomware arrive via vulnerability exploits.

- Bookmark trusted websites and access these websites via bookmarks.

- Download email attachments only from trusted sources.

- Scan your system regularly with anti-malware.

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

Cellular IoT Vulnerabilities: Another Door to Cellular Networks

Cellular IoT Vulnerabilities: Another Door to Cellular Networks AI in the Crosshairs: Understanding and Detecting Attacks on AWS AI Services with Trend Vision One™

AI in the Crosshairs: Understanding and Detecting Attacks on AWS AI Services with Trend Vision One™ Trend 2025 Cyber Risk Report

Trend 2025 Cyber Risk Report CES 2025: A Comprehensive Look at AI Digital Assistants and Their Security Risks

CES 2025: A Comprehensive Look at AI Digital Assistants and Their Security Risks