By CSS Team Researchers:

Cedric Pernet, Jaromir Horejsi, Loseway Lu

With the rise of new technologies, innovations keep appearing that help us with our various activities. A notable system that has emerged in recent years is IPFS system, a decentralized storage and delivery network based on peer-to-peer (P2P) networking and belonging to the emerging “Web3 technologies.”

IPFS allows users to host or share content on the internet at a more affordable price, with availability and resiliency capabilities. Unfortunately, it also provides opportunities for another part of the population: cybercriminals.

In this article, we briefly detail what IPFS is and how it works at the user level, before providing up to date statistics about the current usage of IPFS by cybercriminals, especially for hosting phishing content. We will also discuss emerging new cybercrime activities abusing the IPFS protocol and detail how cybercriminals already consider IPFS for their deeds.

What is IPFS?

IPFS stands for Interplanetary File System. It is a decentralized storage and delivery network, which is built on the principles of P2P networking and content-based addressing.

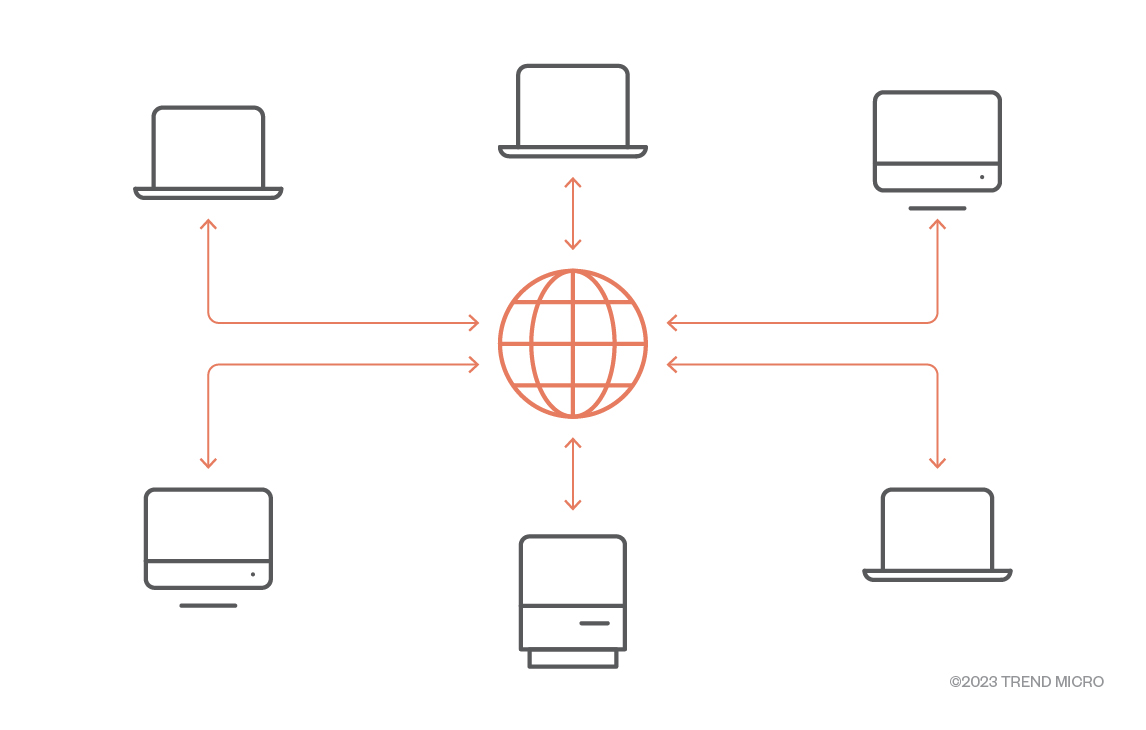

Let’s try comparing it to the way the usual web works. Most of the actual content hosted on the web is served via web servers. In a very simplified view, the way it works on the internet is that different computers request data from different web servers. This data can be web pages, files, or just any content that is accessible via an internet browser. Most of the time, that content is hosted on a single web server, which serves its content to every computer requesting it.

Figure 1. Simplified HTTP(S) protocol

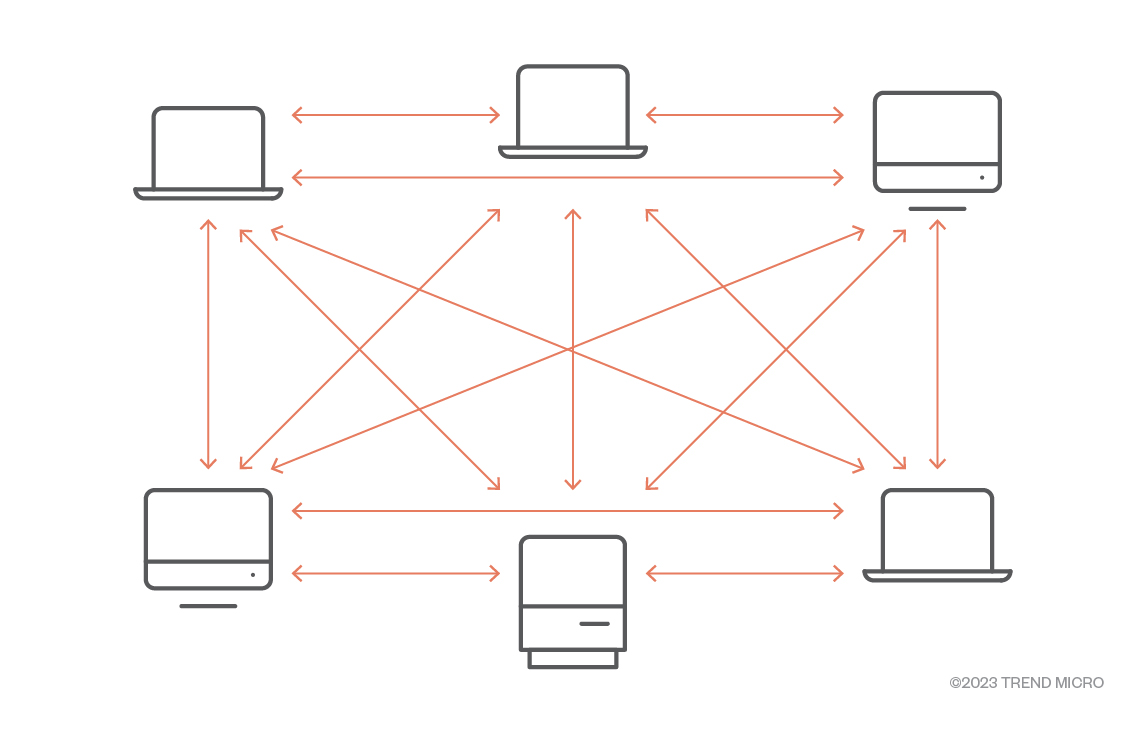

IPFS is a bit different, in the way that there is no central web server providing the data: it can be provided by any of the peers (also called nodes) hosting the data.

Figure 2. IPFS peer-to-peer based model.

To start sharing files on IPFS, users can download and use an IPFS Desktop client, API or use online services.

Once a file is requested by a node that does not have it, the file is copied so it can be shared for others later. This way, more nodes can provide the file. This method makes it possible for any user, including cybercriminals, to create a free account on an online service and start hosting content on the IPFS network, without necessarily running a node on their own infrastructure.

IPFS content identifier (CID)

When browsing the internet, users generally access URLs, such as trendmicro.com, for example. The users’ computer requests the DNS system to know where the data is located and fetches it from that location. Therefore, the client-server model of the web is said to be location-addressed.

In the P2P model adopted by IPFS, a given file might be located on a number of different IPFS peers. The storage of those files is addressed by a cryptographic hash of its content, known as the content identifier (also called CID). The CID is a string of letters and numbers unique to files. A file will always have the same CID, no matter where it is stored. This is why IPFS is said to be content-addressed.

It should also be noted that a file will have a different CID if it is modified in any way.

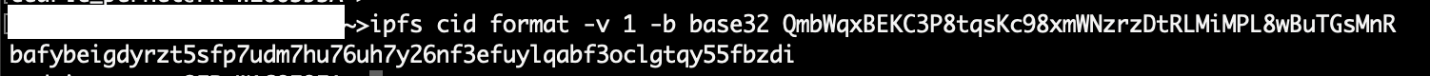

Two versions of the CID exist. The CID v0 format is made of 46 characters and always start with the characters “Qm”, while the CID v1 format uses base32.

It is possible to convert CID v0 to the CID v1 format:

Figure 3. Converting CID v0 to CID v1

IPFS data browsing

CIDs and their corresponding files can be accessed via two ways.

The first way consists of using a browser that handles the IPFS protocol natively. Currently, only Brave browser supports IPFS. The computer runs an IPFS daemon in the background, which the browser uses to natively access the IPFS content.

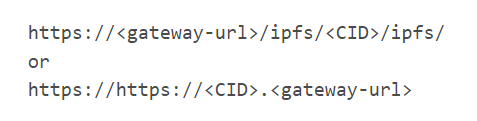

The second way consists of accessing content via so-called “IPFS gateways.” These gateways are used to provide workarounds for applications that don’t natively support IPFS. To summarize, a gateway is an IPFS peer that accepts HTTP requests for IPFS CIDs, allowing users to use their default browsers to access the IPFS content.

The global formats look like this:

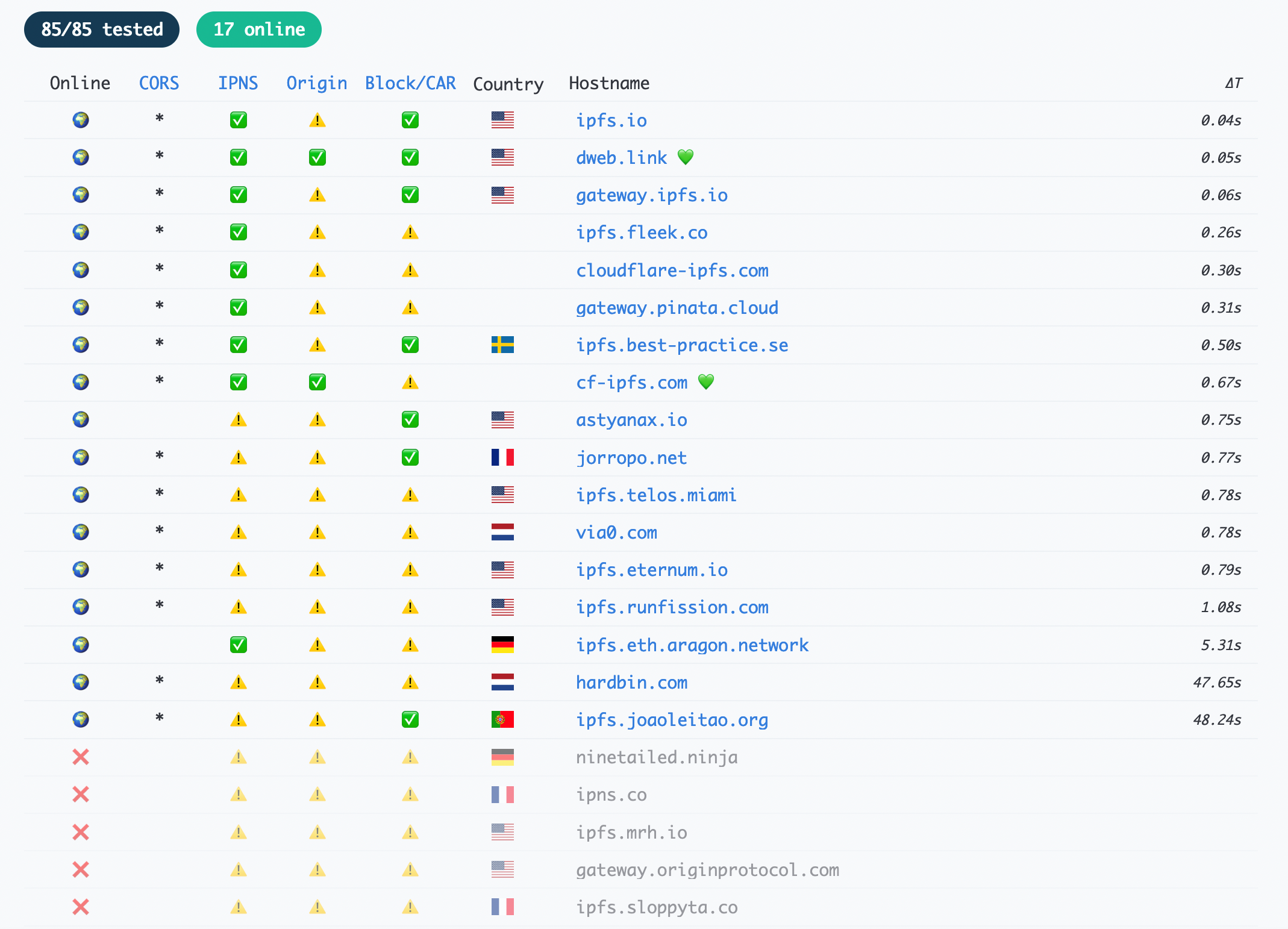

A list of current gateways and their status can be found online at: https://ipfs.github.io/public-gateway-checker/

Figure 4. Screen capture from the public gateway checker

An example of a complete path to access an IPFS content via the ipfs.io gateway looks like this:

- https://gateway.ipfs.io/ipfs/{randomly generated string}

To access the same content via the CloudFlare gateway, the URL would become:

- https://{same randomly generated string}.ipfs.cf-ipfs.com/

Notice how the URL changes because we use a different gateway, but the CID (the randomly generated string) from this example does not change.

Additional parameters might follow that kind of URL depending on the case, just like any web link.

IPFS pinning

Nodes handle the files stored on the IPFS network by caching them and making them available for other nodes on the network. As every node only has a finite cache storage amount, it is sometimes necessary to clean the cache used by the node, which is an operation called the “IPFS Garbage collection process.” During the operation, cached content that it considers no longer needed is removed. This is where IPFS pinning comes in.

IPFS pinning consists of pinning data to ensure that it is not removed from the cache and is always accessible.

IPFS pinning can be done on locally hosted nodes, but pinning services exist to ensure long-term storage. It is interesting for cybercriminals who might use it to have their content stay accessible for longer periods.

IPNS – Interplanetary Name System

IPNS is another protocol, the Interplanetary Name System. It can be seen as a kind of DNS system, but for IPFS. IPNS records are signed using a private key and contain IPFS content path and some other information, such as expiration or version number. IPNS records are published over the Distributed Hash Table (DHT) protocol. Therefore, it needs republishing on a regular basis not to be forgotten by the DHT peers over time.

To summarize, here is an example of an IPNS record:

• /ipns/k2k4r8oid7ncjwgnpoy979brx3r9ellvvwofht57mc9q4jzlxtydalvf

points to

• /ipfs/QmYr5ExzJJncpMNhqzhLjkCrRNgm4UmyX28gcYjt5RLYY8

The IPNS address might be reassigned later to point to other content.

DNSLink

DNSLink uses the TXT records from the DNS protocol to map a DNS name to an IPFS address. This makes it easier for administrators to maintain links to IPFS resources as the DNS TXT record can be changed easily.

DNSLink addresses look like IPNS addresses, except that it uses a DNS name to replace the hashed public key.

As an example, a DNSLink could look like this:

/ipns/example.org

To map the relation, the DNS TXT record needs to be prefixed with dnslink, followed by the hostname.

To further elaborate, here is an example of a DNS TXT record for _dnslink.en/Wikipedia-on-ipfs.org, which resolves as dnslink=/ipfs/bafybeiaysi4s6lnjev27ln5icwm6tueaw2vdykrtjkwiphwekaywqhcjze.

IPFS usage

IPFS can be used for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to:

Data storage and resilience

Resilience relates to the adaptability of a network against isolation. It is also the ability to provide and maintain a service in the case of faults. IPFS provides it in the sense that data is generally stored on several different nodes, making the data less prone to becoming unavailable.

It is also possible to store any kind of data at a very low price on IPFS via services such as Filecoin, for example.

Smart contracts and non-fungible tokens

Smart contracts are programs stored on the blockchain that can be triggered by transactions. While saving data on the blockchain can be expensive, using decentralized storage such as IPFS as the database can reduce costs. For example, one of the common implementations of NFT projects involves storing the metadata and the images (can also be a video, clip, music, etc.) on IPFS, then accessing the data using smart contracts.

Voting

Voting platforms such as Snapshot allows users or companies to use IPFS for storing proposals and user votes or polls.

Document signing

Some online services are available for decentralized versions of document signing. Users can “sign” documents with their wallets. In this usage, the document files are stored on IPFS, and the signatures are stored on the Ethereum blockchain.

Fighting censorship

IPFS might be used by people living in countries that have active censorship technologies. The ability to access the same content via multiple different gateways makes it easier to find a way to reach data without it being blocked. The blocking solutions deployed in such countries might just block one specific gateway and not others, for example.

Paste tools

Just as the website, pastebin.com, is located on the clear web, some paste services do exist on IPFS, like hardbin.com, for example.

Decentralized apps

Decentralized apps or dApps can be built and hosted on IPFS. Available frameworks, such as Fleek, can help developers create such apps.

There are just as many different uses of dApps for IPFS than for the usual clear web.

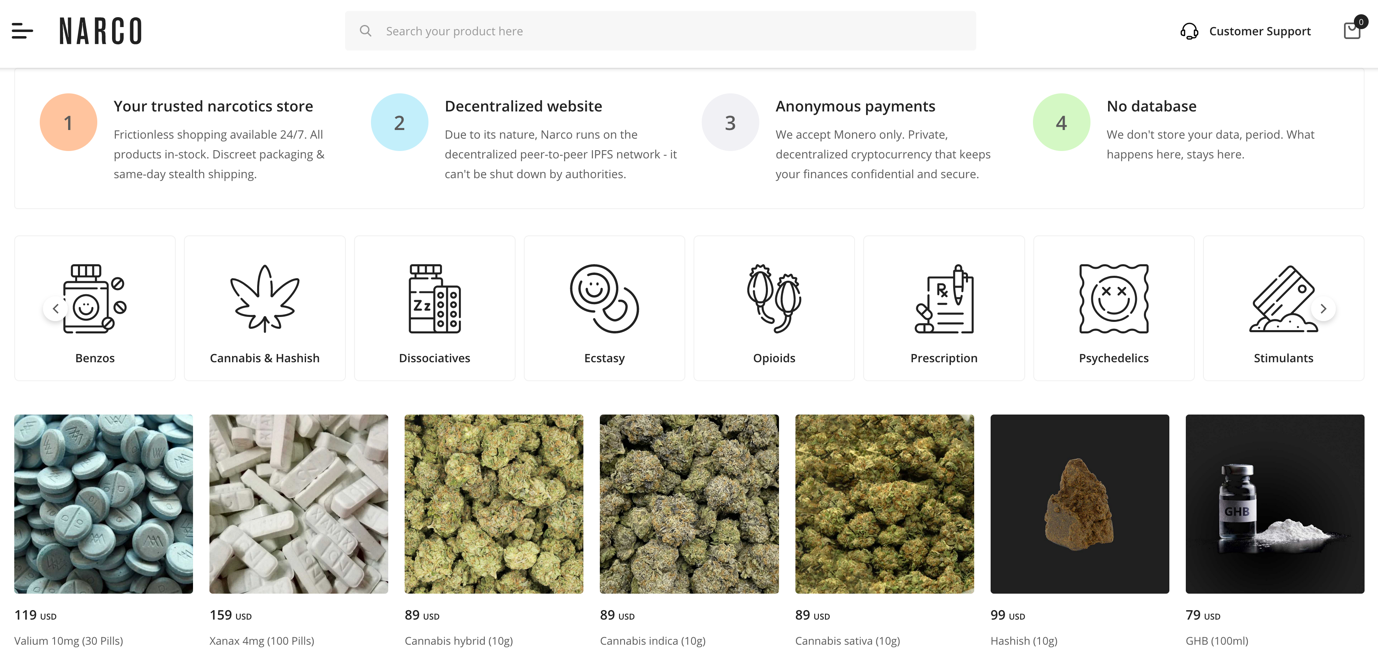

Ecommerce

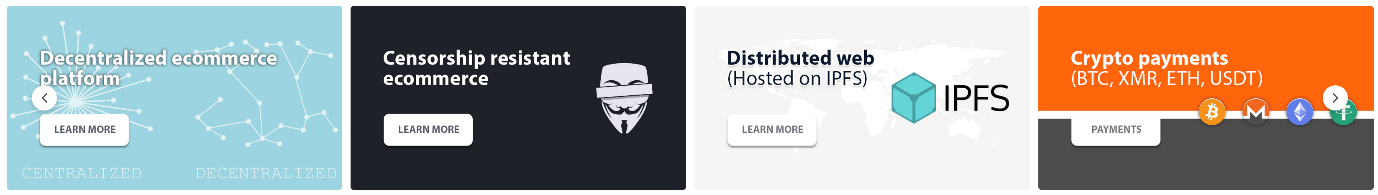

IPFS can be used to run ecommerce websites. During our research, we discovered one ecommerce framework. This particular framework provides hosting on IPFS, and works with cryptocurrencies, which makes it particularly interesting for cybercriminals.

Figure 5. Banner for an ecommerce platform using IPFS and cryptocurrencies.

Cybercrime statistics

We have analyzed several months of IPFS-related cybercriminal activity from our telemetry.

For a few reasons, the method is not exhaustive, and the numbers provided might be lower than reality, yet we still find them very interesting. The first limitation in analyzing our data comes from the fact that some IPFS URLs were just not working at the time of our analysis. Another limitation comes from the data themselves: URLs leading to password-protected files (mostly archive files) could not be analyzed, thus we cannot know the content of those archives. Finally, some of our customers do not want to send back any detection data, so our analysis can’t be 100% accurate.

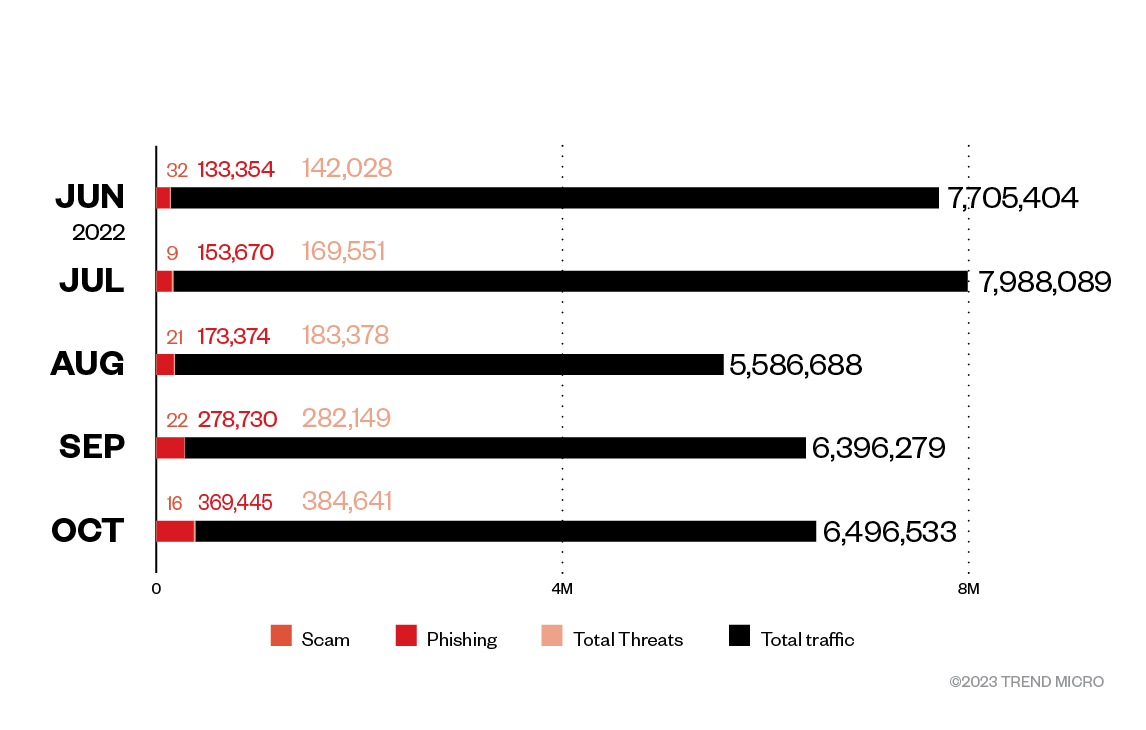

The results we obtained seem fairly constant from one month to the other in the observed range, from June to October 2022.

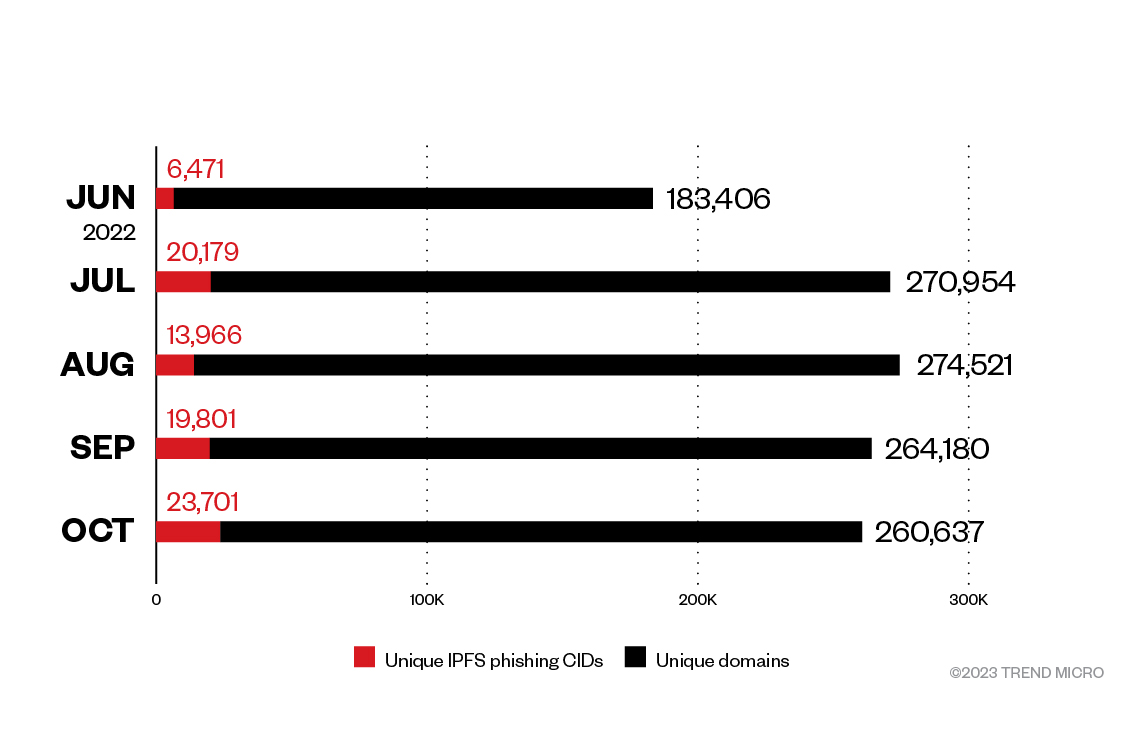

Figure 6. IPFS URL hit statistics

As can be seen in figure 6, the total number of IPFS analyzed in our telemetry per month ranges from 5.5 million to 7.9 million hits.

The number of threats posed by IPFS in our data steadily increases. While it represented 1.8% of the global IPFS traffic in May 2022, it now counts for almost 6% of the traffic. We believe with high confidence that it is still going to increase in the future

Scams

We found very few IPFS-hosted content related to scams. The content we found, which was never more than 0.02% of the threats, consists of images used by scammers such as those used for lottery scams, or more recently, in Bored Ape NFT scams. They are all related to long-time existing types of fraud.

Phishing

Phishing consists of enticing unsuspecting users into providing their credentials to cybercriminals, generally via phishing emails, SMS, messages on social networks, private messages, etc. leading to phishing pages hosted on the internet.

Those phishing pages generally pretend to be a mailbox access or just any kind of online services in order to make victims fill it with their login credentials, which cybercriminals can later use for different fraudulent purposes.

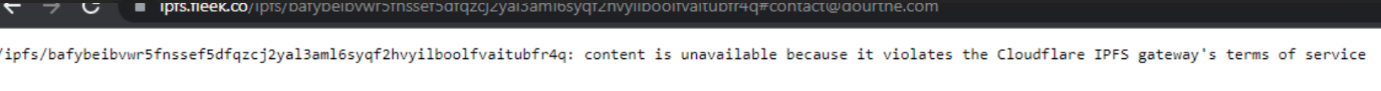

While phishing pages are relatively easy to set up, its main weakness resides in the hosting of such pages. As soon as a phishing page is reported, it is generally blocked within minutes by security solutions and taken down by the hosting company.

Using IPFS to host such phishing pages makes sense since the pages will be harder to take down.

Figure 7. Some gateways do take down phishing content, but simply switching the gateway allows access to the same phishing site

The majority of IPFS threats we analyzed are phishing threats. As can be seen in Figure 6, phishing occurs in more than 90% of the global IPFS threats for every month we analyzed, reaching 98.78% in September 2022.

Phishing statistics: IPFS vs non-IPFS

Figure 8. IPFS vs non-IPFS phishing pages hosting

To fully understand the threat of IPFS phishing, it needs to be compared to usual phishing using the web. While percentage of IPFS vs. non-IPFS might seem low (between 3.5% and 9% of phishing threats), the volume is a growing concern.

In October 2022, unique IPFS CIDs represented 9% of the global phishing threat, yet it still represents more than 23,000 unique pages hosted on IPFS for that month. We believe these numbers are still going to increase in the future, and confident that IPFS phishing will count for more than 10% of the phishing threat in the coming months.

It is also difficult to determine the real impact of IPFS phishing, as these statistics only reflect a number of unique domains/CIDs, but not the number of emails spreading each of those. A unique domain might be triggered by millions of emails while another one might only spread to a few thousand victims.

IPFS phishing: stolen data still on the usual web

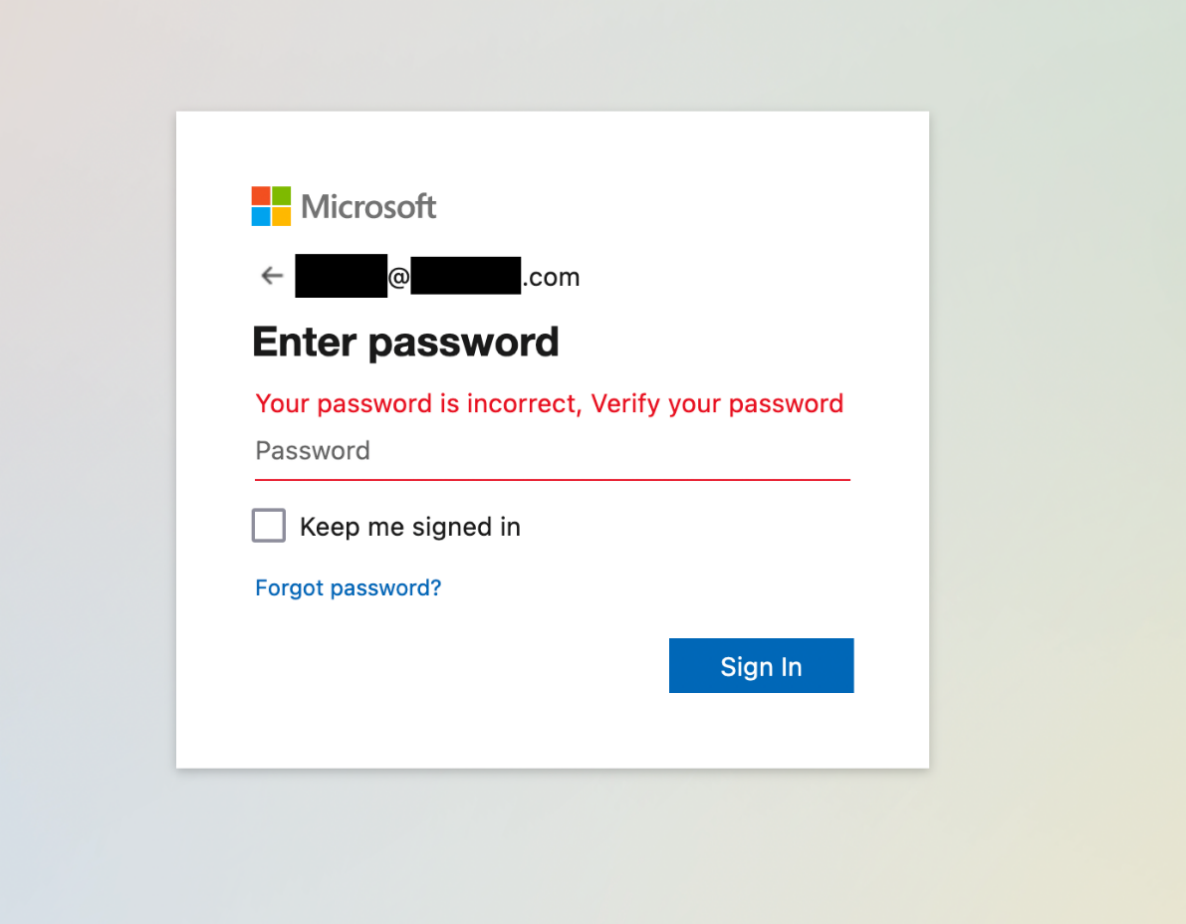

Figure 9 shows an example of a phishing page we have seen in the wild, available on IPFS:

Figure 9. Phishing example hosted on IPFS (Recipients email address has been removed)

Unsuspecting users are led to that page via an initial email that contains an IPFS link to the page. The link contains one parameter transmitted to the page, which is the email address of the target.

bafybeicsapdb6iapble5huh6ph5gkjl75ugck7gnx4ih4w25zb[.]ipfs[.]w3s.link/aws.html?email=

Yet when analyzing the HTTP POST request headers sent by a victim who would click on the “Sign In” button, we see the data goes to a usual URL on the web:

POST /wp-content/plugins/ioptimization/awy/df.php HTTP/2

Host: < REDACTED >.immo

User-Agent: < REDACTED >

Accept: application/json, text/javascript, */*; q=0.01

Accept-Language: fr,fr-FR;q=0.8,en-US;q=0.5,en;q=0.3

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 90

Origin: https://bafybeicsapdb6iapble5huh6ph5gkjl75ugck7gnx4ih4w25zb[.]ipfs[.]w3s.link

DNT: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Referer: https://bafybeicsapdb6iapble5huh6ph5gkjl75ugck7gnx4ih4w25zb[.]ipfs[.]w3s.link/

Sec-Fetch-Dest: empty

Sec-Fetch-Mode: cors

Sec-Fetch-Site: cross-site

The data sent by the user is actually transmitted to a PHP script hosted on a compromised website

This might be our most interesting discovery here: we found no IPFS phishing page that would send the data to IPFS. All of the phishing pages we analyzed do send the stolen data to usual servers on the web.

Phishing emails

Our telemetry reports a daily activity of about 27,000 unique emails containing phishing IPFS links, leading to phishing pages hosted on IPFS. This activity covers approximately 30 different phishing campaigns per day.

< TARGET EMAIL ADDRESS > Download your documents via WeTransfer < DATE >

Reminder: Please DocuSign:XXXXXX DRAFT XXXXX.docx

Mail Password Update Notification For < TARGET EMAIL ADDRESS >

Completed: Letter of Acceptance for Contract Ref. No. 2022/XXX/XXXXXXXXXXXX

< COMPANY NAME > Insurance Renewal Quote

< TARGET EMAIL ADDRESS > you have new shared Invoice document

Password for < TARGET EMAIL ADDRESS > expires today < DATE >

Your < COMPANY WEBSITE URL > Account storage is 99% full

As can be seen in Figure 12, the phishing email topics are no different from the ones on the clear web that use common social engineering methods.

Malware

So far, we have seen very few cybercriminals making use of IPFS to host malware.

We found 180 different malware samples through the last five months, which is incredibly low compared to the numerous samples we see every month.

We found very few ransomware on IPFS, most of those we found were older ransomware families.

Amongst the usual low-level malware that you might expect on the internet, such as adware and potentially unwanted applications (PUA), we found a few more serious threats on IPFS.

Information stealers and remote administration tools

Info stealers and malicious RATs are amongst the biggest threats on the internet, and we found a few families on IPFS.

| Malware Family | Number of unique samples |

| Agent Tesla (Trojan.MSIL.AGENTTESLA.THCOCBO) | 55 samples |

| Formbook (Trojan.Win32.FORMBOOK.EPX ,Trojan.W97M.FORMBOOK.AQ) | 10 samples |

| Remcos RAT (Backdoor.Win32.REMCOS.TICOGBZ) | 9 samples |

| Redline Stealer (TrojanSpy.MSIL.REDLINESTEALER.YXBDN, TrojanSpy.Win32.REDLINE.X, TrojanSpy.MSIL.REDLINESTEALER.N) | 6 samples |

| Other various RATs/infostealers | 3 samples |

Table 1. Malware family and their samples on IPFS

In addition to malware, we also found common tools used for legitimate and non-legitimate purposes hosted on IPFS, such as proxying tools or scamming tools, and file binders.

Finally, we could find seven cryptominer samples that are hosted on IPFS, which might be used for legitimate or illegitimate purpose, depending if they are run legally or on compromised machines.

IPFS in underground forums

IPFS discussions

Just as with any new technology, IPFS is being discussed in cybercriminal underground forums. The discussions range from non-technical topics, often produced by low skilled cybercriminals with questions like “what is IPFS?” to real technical conversations about IPFS infrastructure.

Some of those cybercriminals were criticizing the protocol, mostly by emphasizing that it is really slow and cannot be used for all purposes, while others were more enthusiastic and already using it.

One of the IPFS adopters asked on the Lapsu$ Chat on Telegram, however, did not get an answer:

“Lapsus team, how feasible would it be to setup an ipfs node on the server you’re currently seeding from? Data would be quickly cached on cloudflare for free and downloads would be super fast.”

IPFS for data sharing amongst cybercriminals

Cybercriminals often need to share files, cybercrime methods/tutorials, or even just screenshots on the underground forums, and use free data hosting services such as MediaFire or Mega for these purposes. Some might also use hosting on the Tor union network.

We have seen an increasing number of cybercriminals using IPFS to store such content and share it with their peers since 2021.

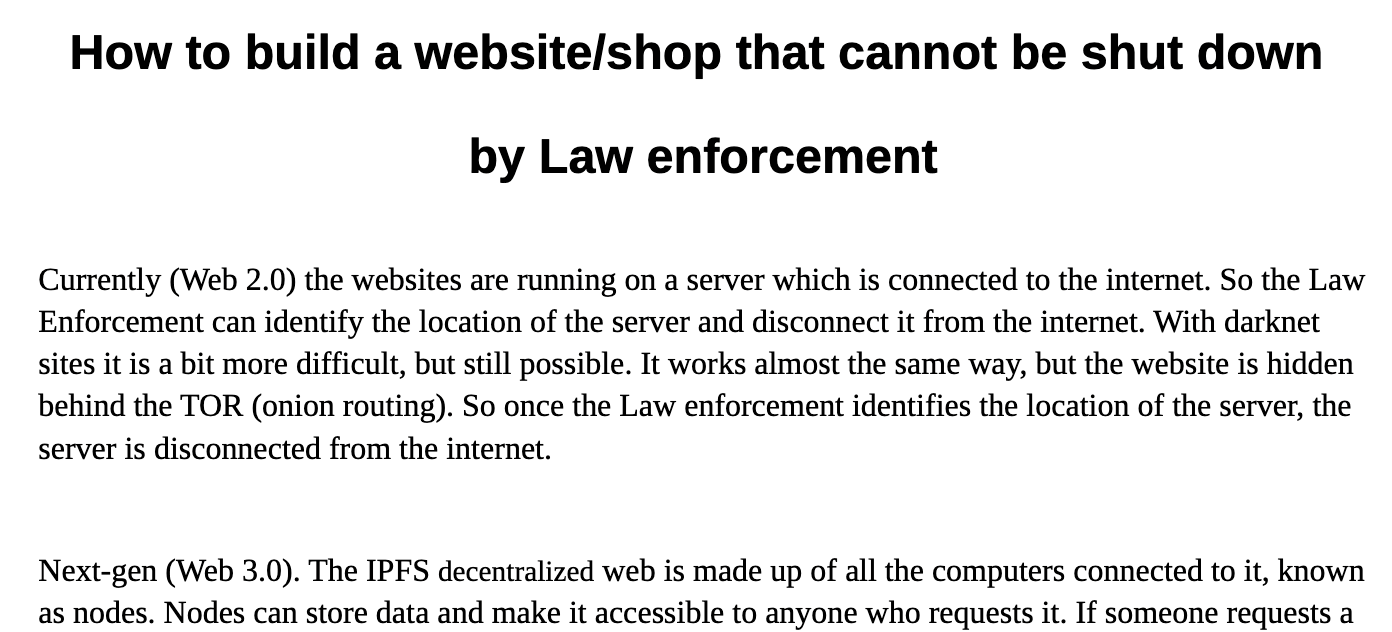

As an example, we saw one user share a PDF file on IPFS in November 2022 that is actually a tutorial on “How to build a website/shop that cannot be shut down by Law enforcement.”

Figure 10: Sample content from a PDF file hosted on IPFS and shared amongst cybercriminals

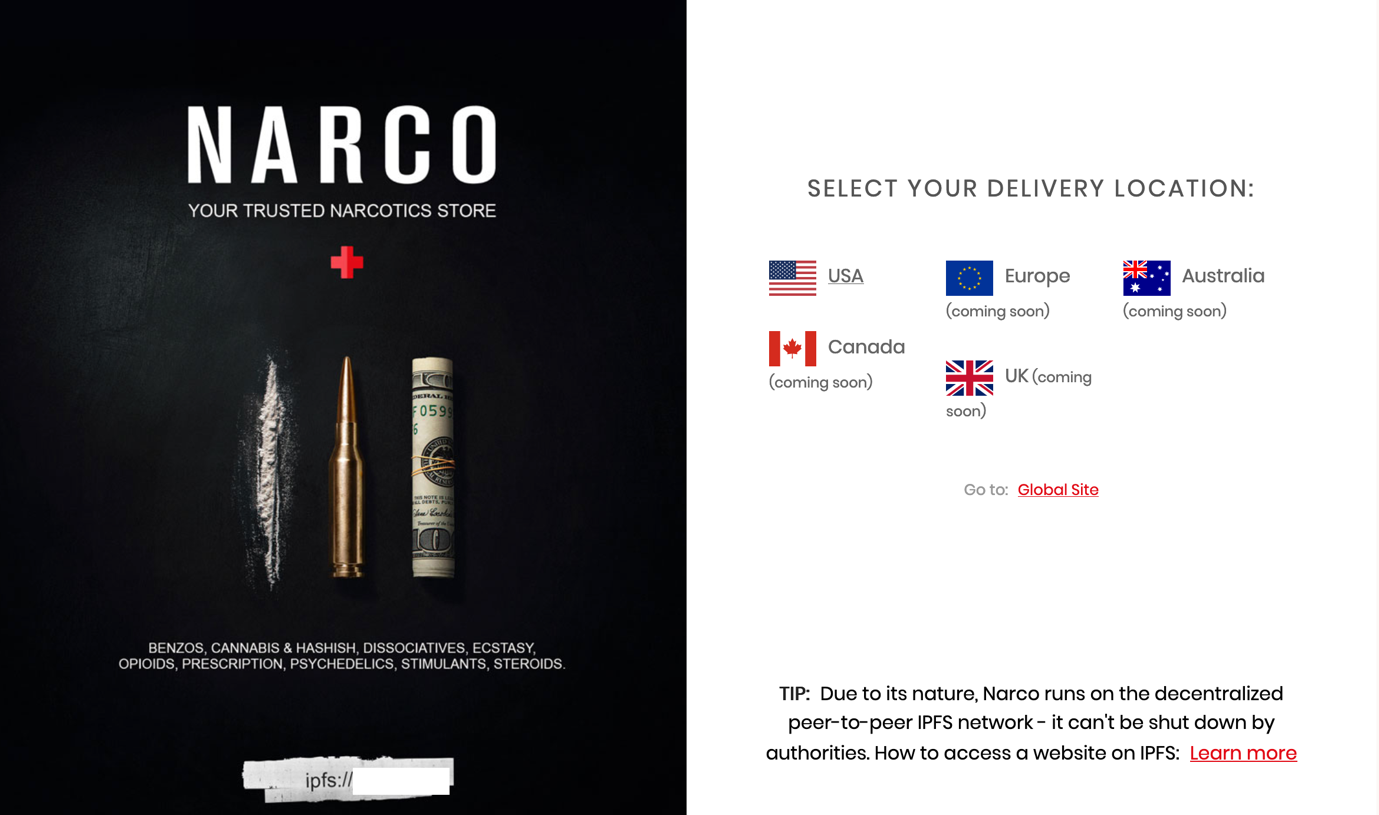

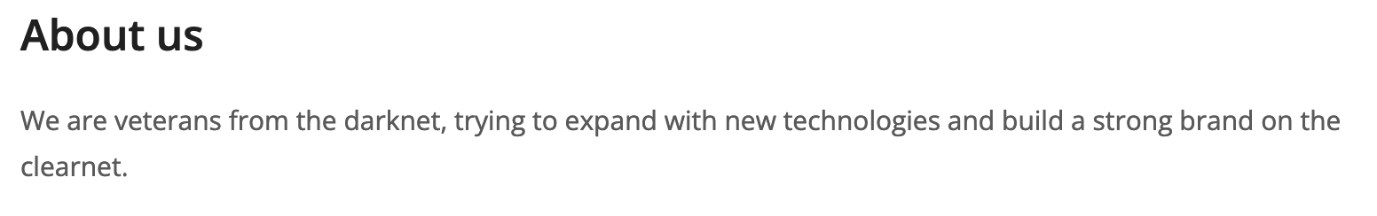

IPFS for illegal content hosting

We found advertisements in underground forums for a few illegal commercial services that were hosted on IPFS.

Figure 11. Entrance page for a website that sells illegal drugs hosted on IPFS.

Figure 12. Screenshot of a website that sells drugs found on IPFS

The website owners describe themselves as veterans from the Darknet interested in new technologies.

Figure 13. Description from the website’s About us page

Conclusion

IPFS and its related IPNS are protocols that can be abused by cybercriminals, just like any other protocol.

Cybercriminals with average or low skill levels will probably not use much of the technology, mostly because it needs some preparation and knowledge to be used efficiently. Yet, the more advanced malicious actors might see opportunities in it. Backed by the fact that they are already talking about it in their underground forums. Additionally, some of them are already using it for hosting and conducting their deeds.

Ecommerce looks to be growing in the IPFS environment and this has definitely been exploited by the cybercriminals. They have set up stores selling illegal goods, and in the event that one node is down, another will take its place, providing resiliency. However, we should also take note of the increase of phishing sites and how it works well in IPFS. Other threat actors are also using the system to host malware. We also expect some threat actors to create their own IPFS gateways and run nodes to keep their content online as much as possible.

While IPFS is a popular choice when it comes to Web 3.0 decentralized storage, there are more options. We expect threat actors to explore other Web3 storages for their operations moving forward. In this sense, we must become more vigilant whenever a new technology appears, because while it can benefit a lot of people, cybercriminals can also see opportunities.

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

- Unveiling AI Agent Vulnerabilities Part II: Code Execution

- Unveiling AI Agent Vulnerabilities Part I: Introduction to AI Agent Vulnerabilities

- The Ever-Evolving Threat of the Russian-Speaking Cybercriminal Underground

- From Registries to Private Networks: Threat Scenarios Putting Organizations in Jeopardy

- Trend 2025 Cyber Risk Report

Cellular IoT Vulnerabilities: Another Door to Cellular Networks

Cellular IoT Vulnerabilities: Another Door to Cellular Networks AI in the Crosshairs: Understanding and Detecting Attacks on AWS AI Services with Trend Vision One™

AI in the Crosshairs: Understanding and Detecting Attacks on AWS AI Services with Trend Vision One™ Trend 2025 Cyber Risk Report

Trend 2025 Cyber Risk Report CES 2025: A Comprehensive Look at AI Digital Assistants and Their Security Risks

CES 2025: A Comprehensive Look at AI Digital Assistants and Their Security Risks