Mobile Malware: 10 Terrible Years

We all just want to enjoy using our mobile devices without worries, which would only be possible if we didn’t have to think about malware. Despite the hassle they bring though, mobile malware should be appreciated for what they’ve done. That doesn’t mean celebrating the fact that cybercriminals use them to prey on mobile users for profit. Rather, they made us smarter, savvier technology users. Because 2014 marks mobile malware’s tenth year anniversary, let’s take a trip down memory lane to see just how much they’ve evolved.

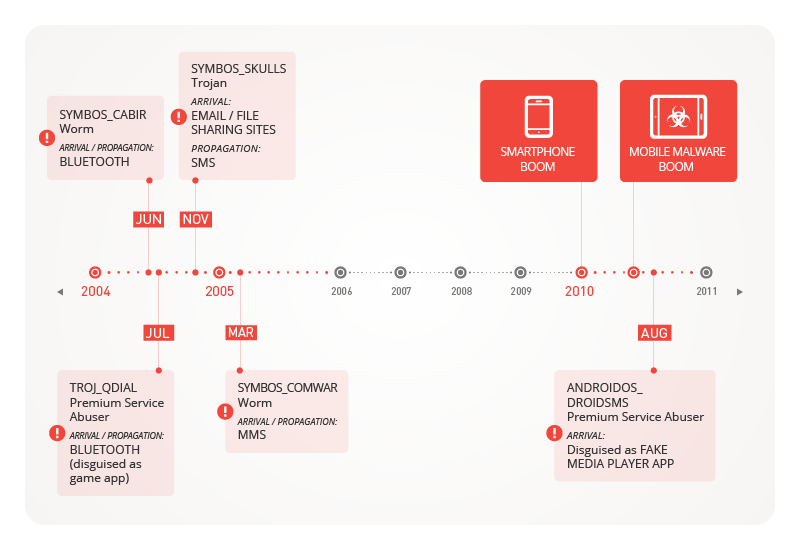

Figure 1: Mobile malware these past 10 years

Presmartphone Era

2004 saw SYMBOS_CABIR, a proof-of-concept (PoC) piece of mobile malware created by “Vallez,” a member of the 29A group of virus writers. CABIR variants were benign but certainly annoying. They made infected devices, specifically Nokia smartphones, display the message “Caribe” on-screen every time they’re turned on. They were also quickly picked up by other coders and made more malicious, armed with more annoying pop-up messages and other features.

Figure 2: SYMBOS_CABIR installation prompt

That same year, premium service abusers started emerging. We saw TROJ_QDIAL, a Trojanized version of the game, “Mosquitos,” which sent premium-rate text messages from compromised Symbian-based devices. Like other premium service abusers, this charged users exorbitant costs.

Later that year, particularly in November, SYMBOS_SKULLS made its debut. It made its way into mobile devices through file-sharing sites and emails and deleted key files, rendering them useless. SYMBOS_COMWAR followed a year after, becoming the first piece of malware that spreads via Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) messages disguised as freeware ad links.

Smartphone Era

It wasn’t until the smartphone era began in 2010 when mobile malware really took off both in terms of quantity and money-stealing capability. After Apple made smartphones mainstream with the success of the iPhone® and Google’s Android™ OS made smartphones available to a wider range of users, cybercriminals realized they could milk a huge cash cow.

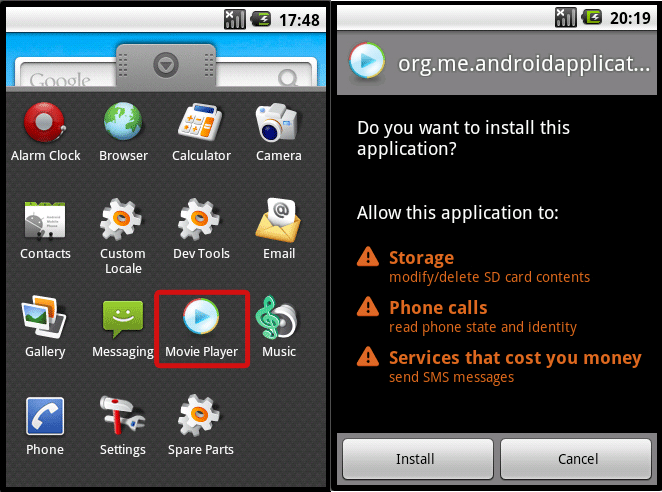

The first known cybercriminal attack came in the form of a Russian SMS fraud app, also known as ANDROIDOS_DROIDSMS.A, emerged in August 2010. Much like QDIAL, it could send premium-rate text messages from infected Android devices without the user’s authorization or knowledge.

Figure 3: ANDROIDOS_DROIDSMS.A permission request

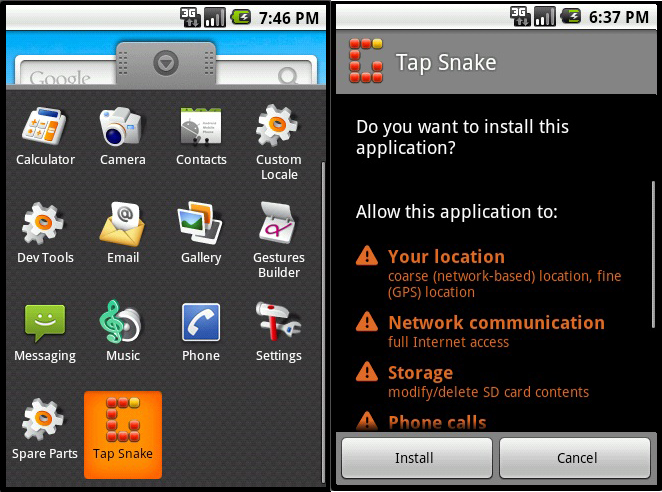

Barely a month after, we saw another Android Trojan masquerade as a game called “Tap Snake,” also known as ANDROIDOS_DROISNAKE.A. It could transmit an infected phone’s Global Positioning System (GPS) location to attackers, which made it the first “spying” app.

Figure 4: ANDROIDOS_DROISNAKE.A permission request

iOS devices weren’t safe from threats either. In August that same year, we saw the first iOS malware, the Ikee worm, also known as IOS_IKEE.A. This piece of malware could only affect “jailbroken” iPhones. It modified an infected device’s background to a picture of 80s pop sensation, Rick Astley, and played his song over and over. It spread by taking advantage devices that used the default Secure Shell (SSH) password. While not necessarily malicious, IOS_IKEE.A was soon modified to steal the banking information of customers of the ING Bank of Netherlands.

Troubling Trends

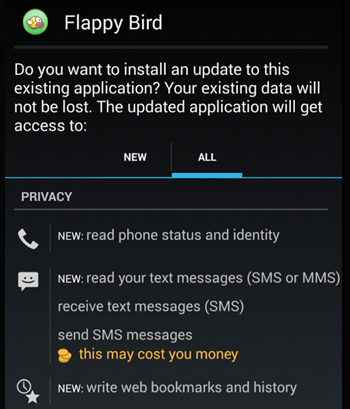

The “pioneer” malware discussed above served as a preview of the trends that now permeate the mobile threat landscape. ANDROIDOS_DROIDSMS, for instance, was a typical premium service abuser. And as our annual 2013 security roundup shows, premium service abusers are the most commonly found Android malware today.

Another example, ANDROIDOS_DROISNAKE.A, was a spying tool that masqueraded as a popular game. It was one of the Trojanized apps that was made available in app stores.

We’ve seen many instances when cybercriminals created fake versions of games throughout the years, including Angry Birds and Flappy Bird. Trojanized apps came with an array of data-stealing routines, siphoning personal information off infected devices and sending stolen data to attackers.

Figure 5: Fake Flappy Bird permission request

Cybercriminals have also ventured into exploiting mobile platform bugs as soon as these are found. The Android master key vulnerability was one of these. It allowed an attacker to modify a legitimate app’s parameters without user authorization. Attackers exploited this with a supposed update to a certain Korean bank’s app. Once executed, the update turned the legitimate app into a data stealer that sends the victim’s online banking credentials to the attackers.

We’ve seen some surprises, too. ANDROIDOS_KSAPP.A, which allowed a remote user to run malicious commands was discovered at the start of 2013. It took complete control of an affected device, much like a backdoor would on a PC. This happened the same time a million-strong smartphone botnet was rumored to have been wreaking havoc on China’s smartphone ecosystem.

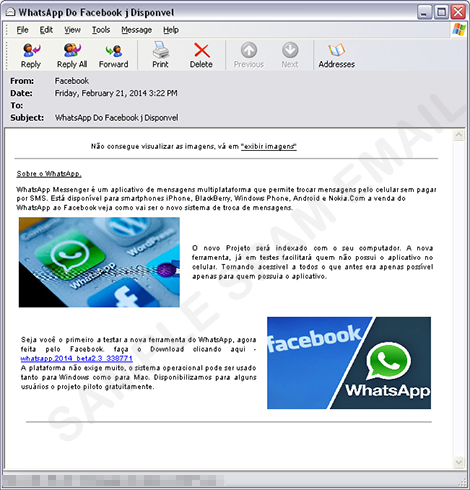

More sophisticated routines and more damaging vulnerabilities weren’t the only disturbances we’ve seen though. The means by which mobile malware spread also evolved. Cybercriminals tailored their attacks to affect multiple mobile platforms at once, as seen in September 2013 when a spam notifying users they received a new voicemail from WhatsApp circulated.

Figure 6: WhatsApp spam sample

This threat didn’t discriminate in terms of victim. The piece of malware could be downloaded onto an Android or iOS device. iOS device users fared better though, as they could, by default, only download apps from the App Store

SM. iOS downloads only succeeded on jailbroken devices. Android devices were, on the other hand, infected withANDROIDOS_OPFAKE.CTD.

Multiplatform attacks can be considered another step in the mobile malware evolution. They also proved that cybercriminals constantly improved tools and tactics to keep up with the technologies they take advantage of. That doesn’t mean they just get rid of tried-and-tested means to victimize users. In fact, old tricks that still work live on for long periods of time.

Beyond 10 Years

While mobile malware have certainly been around for some time now, cybercriminals only started to ramp their production up in 2012. But mobile malware distributed online are’t the only threats users should be wary of. We’ve seen cases wherein newly sold devices came bundled with malware as well. It’s also interesting to note that the number of mobile threats has surpassed that for PCs after a very short time. As of last count, the number of malicious and high-risk Android apps has reached more than 1.4 million. We expect this to keep rising.

As the shift from PCs to mobile devices continues, cybercriminals will launch more and more mobile attacks. Recent research even revealed a budding mobile underground market in China. We believe cybercriminals will continue to create and spread fake versions of the most popular apps and that premium service abusers will remain the most common mobile malware. But we also believe that new malware will increasingly take advantage of faulty built-in features. We may soon see incidents wherein attackers abuse connectivity features to turn mobile devices into espionage gadgets. We may, for instance, see more malware like ANDROIDOS_DENDROID.HBT turn a victim’s smartphone camera on to discreetly capture audio or video. More vulnerabilities will be discovered and exploited and mobile banking transactions will constantly be targeted.

Mobile malware will continue to pose security issues as long as cybercriminals view mobile device users viable and lucrative targets. That’s not going to change anytime soon, especially as app use becomes more and more integrated into daily tasks like online shopping and banking. To stay protected, consumers and business owners should recognize the need for mobile security more than ever. We’ve had 10 years to learn, let’s not waste another 10.

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

Recent Posts

- Azure Control Plane Threat Detection With TrendAI Vision One™

- Forecasting Future Outbreaks: A Behavioral and Predictive Approach to Proactive Cyber Risk Management

- Fault Lines in the AI Ecosystem: TrendAI™ State of AI Security Report

- The Industrialization of Botnets: Automation and Scale as a New Threat Infrastructure

- From Holiday Snap to Custom Scam in 30 Minutes: How AI Turns Public Photos Into Targeted Attacks

Fault Lines in the AI Ecosystem: TrendAI™ State of AI Security Report

Fault Lines in the AI Ecosystem: TrendAI™ State of AI Security Report Azure Control Plane Threat Detection With TrendAI Vision One™

Azure Control Plane Threat Detection With TrendAI Vision One™ The AI-fication of Cyberthreats: Trend Micro Security Predictions for 2026

The AI-fication of Cyberthreats: Trend Micro Security Predictions for 2026 Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One

Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One